UK lags behind peer countries in discharging hospital patients, study finds

The UK lags behind many comparable countries in the speed at which it discharges medically fit patients from hospital owing to under-investment and flawed co-ordination across the health and care system, according to a new report.

Moving patients out of hospital and into the community to free up much-needed bed space has long been a key pillar of the NHS’s strategy, with Prime Minister Rishi Sunak pledging to cut waiting lists for routine care ahead of the election expected next year.

But while countries such as the Netherlands and Denmark have successfully shifted more care to community settings, the Nuffield Trust said on Tuesday that “progress and delivery on these ambitions has been minimal” in England.

“Insufficient capacity in community health and care services” had “beleaguered the system for years”, the think-tank added in its report, which drew on both international data sets covering the UK and detailed analysis of England’s health service.

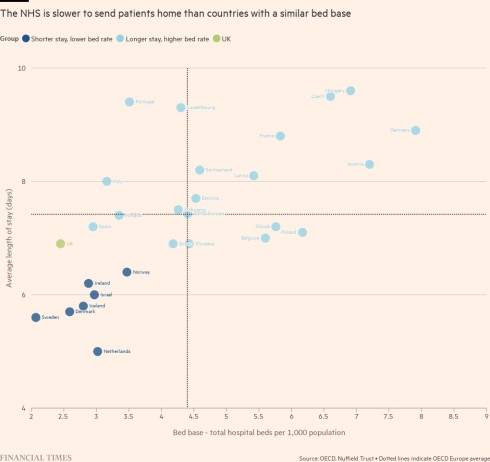

While average lengths of hospital stay for UK patients compared well with other countries belonging to the Paris-based OECD, researchers found the country appeared to underperform when measured against other health systems with a similarly low number of acute beds.

The NHS seemed to be slower in sending patients home than countries including Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands, which all have a similar bed base, they noted.

Difficulties in discharging patients deemed fit enough to leave has significantly inflated waiting lists for non-urgent treatment in England. Cutting the record backlog of 7.6mn took on fresh political urgency after Sunak made it a “people’s priority” in January, inviting voters to judge him on whether lists are falling when they next go to the polls.

Nigel Edwards, Nuffield Trust chief executive, said the study showed that the NHS focused disproportionate investment and attention on measures to stop hospital admissions and too little on “the ‘back door’ . . . sorting out the patients who shouldn’t be in hospital and could be cared for better, more effectively and more safely in other places”.

Data from NHS England shows that in the year to December 2022 the number of patients in hospital who were fit enough to leave but had yet to do so jumped by 27 per cent. Among those admitted for three weeks or more, 70 per cent were awaiting community health and social care services, such as rehabilitation, home care, or a nursing home place, the study noted.

Yet it found that the proportion of the NHS budget spent on primary care and community services fell in the three years to 2018-19.

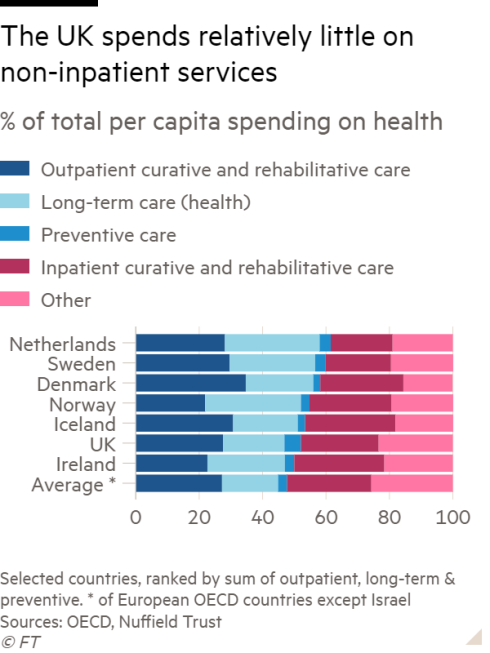

The Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark and Norway respectively allot 62 per cent, 60 per cent, 58 per cent and 55 per cent of their total spend on health per head to outpatient, prevention and long-term healthcare compared with the UK’s 52 per cent, the researchers found.

Another key distinction is that in many other countries, local municipalities are responsible for community health and social care services, whereas in England accountability tends to be split between local councils and the NHS.

Edwards pointed to a “vicious cycle” in which patients were discharged from hospital without the necessary support to continue their recovery, meaning they were far more likely to be readmitted.

He acknowledged that the community-centric approach was not a panacea, however. Some countries’ experiences have highlighted that structural shake-ups may not deliver their intended effects unless supported by ample funding.

In a 2007 shake-up, Denmark consolidated hospitals into larger, regionalised units, while smaller hospitals were converted into intermediate care or “step-down” facilities.

The report noted that over the past decade, the share of Denmark’s health expenditure invested in inpatient services fell by 15 per cent as more care has shifted to outpatient settings.

Karsten Vrangbæk, director of the Centre for Health Economics and Policy at the University of Copenhagen, said Danish politicians had employed “a sort of strong rhetoric” that centralising hospitals would allow more specialised services. “So it was really sold as raising the quality.”

However, he noted that giving municipal governments more powers had exposed differences in the levels of funding and staffing each was able to command, although a redistribution mechanism from richer to poorer municipalities and tighter regulation from the state had reduced the level of variation, he added.

In the Netherlands, Nuffield noted, “evaluations of long-term care reforms concluded that smaller municipalities had insufficient capacity to carry out their new responsibilities properly”.

Madelon Kroneman, senior researcher at the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research, suggested the Dutch government had overestimated the savings that would come from decentralising care as it sought to control “unsustainable” growth in healthcare spending.

With costs still rising, ministers had attempted to limit the number leaving hospital for expensive long-term care homes, but doing so had meant families were increasingly expected to find, or provide, the support their loved ones needed, she warned.

Noting that the new approach had also put more pressure on GPs, Kroneman said there was consensus across the sector that there should be a focus on “the right care in the right place . . . [but] what that ‘right place’ is is not yet clear”.

The Department of Health and Social Care said it was “working to ensure patients leave hospital as soon as they are medically fit” and that “the number of patients each day who are ready to be discharged has reduced by approximately 2,800 in England since January”.

“We are investing a record £1.6bn to support this on top of £700mn to ease hospital pressures over last winter and buy thousands of extra care packages and beds,” it said.

NHS England said it had “rapidly expanded the use of out-of-hospital care” and was “increasing the number of patients treated at home or in the community”.

It added that treating patients at home via “virtual ward beds” could help them avoid “unnecessary hospital admissions . . . [and] recover faster where they are most comfortable”.

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Sarah Neville