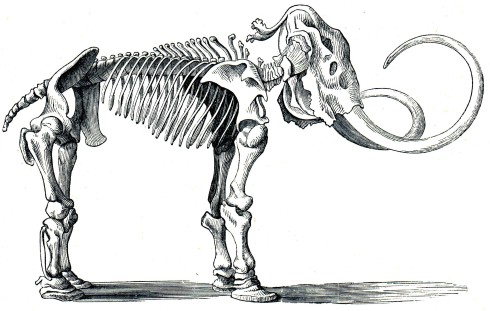

Woolly idea: a start-up’s wild plan to resurrect the mammoth

George Church has co-founded almost 50 companies based on experiments in his genetics lab, from tackling age-related diseases to creating pig organs to be used in human transplants.

But his latest project, Colossal Biosciences, is his most outlandish yet. The Texas-based start-up is aiming to spin off businesses and license technologies to fund bringing the woolly mammoth, the Tasmanian tiger, and the dodo back from extinction.

Its plan is to use gene editing to change the embryos of familiar animals until they resemble the lost species and it wants to create its first version of a mammoth — a gene edited elephant embryo born to an elephant mother — by 2028. Church said the timeline was “ambitious” but “not impossible”.

Since the business was co-founded by Church in 2021, it has raised $225mn from big name investors and celebrities including venture capitalist Peter Thiel, entrepreneur Thomas Tull and Paris Hilton.

It has already spun off biotech software company Form Bio last year, raising $30mn and it hopes to capitalise on other technology developed along the way to help fund its mammoth project.

It is also anticipating revenue from media partnerships telling the story of a project that some have compared to Jurassic Park.

But according to Church: “The main business isn’t endangered species. We may even give a lot of that away just for conservation and goodwill. I think the main business is technology development.”

For years, Church said he did not think anyone would fund his pet project to resurrect the woolly mammoth. Then in 2015, Thiel, the co-founder of PayPal and Palantir, offered him $100,000 for the work over breakfast.

“He just said, ‘What are your top three dreams?’ and I thought he would definitely bite on ageing reversal. But he didn’t. I didn’t think he would bite on mammoths, but he did,” Church said.

In 2018, Church travelled to the Pleistocene Park experimental nature reserve in Siberia, where he was working with Russian scientist Sergey Zimov on a plan for the mammoths to eventually be released into the wild.

Colossal believes that bringing back mammoths could help restore the arctic tundra, preventing the thaw and release of stored greenhouse gases.

The project faces two huge challenges in particular. The first is to increase the number of gene edits that can be done at once, a process known as “multiplex editing”, to get as close as possible to creating a mammoth from an elephant embryo.

The second is to create a system to incubate mammoths in artificial wombs. Matt James, chief animal officer at Colossal, who joined after a career in zoos where he specialised in looking after elephants, said the number of reproductive females in a population is always the limiting factor in scaling up endangered species populations.

“If you have an artificial womb, then suddenly you can start to scale the population and help recover populations very quickly,” he said.

Critics say the challenges make the project near impossible, or not ecologically sound.

Matthew Cobb, a professor of zoology at the University of Manchester, said the plans involve creating “a vaguely mammoth-ish elephant, or a vaguely dodo-ish pigeon”.

“They are not de-extincting any animal, they are using the power of genetic engineering, they claim, to create a weird hybrid,” he said.

Colossal said it was not trying to make exact clones but to create a species that has specific traits that makes it unique.

Cobb added it would also be hard to build a breeding population, which would require at least several hundred animals to ensure genetic diversity.

Stuart Pimm, an ecologist at Duke University in North Carolina, who studies present day extinctions, said a single woolly mammoth would struggle to survive — and a sufficient herd would need a huge amount of space.

“If you had a woolly mammoth, the only thing you could do is put it in a cage. That seems to be outrageous, you’ve done all this effort to create something for a peep show,” he said. “So how many woolly mammoths would you need? You’d need 50, maybe 100, and you’d need a thousand square kilometres in which to put them.”

James agreed that the mammoths would be “highly social” and need a “strong herd structure”, so Colossal plans to create genetically diverse herds of mammoths to provide it. He said the company is working on identifying rewilding sites with sufficient space for a herd, including conversations with US state governments.

Colossal said it was also working with governments on ideas for preserving endangered species.

Ben Lamm, the serial entrepreneur who is Colossal’s co-founder and chief executive, said Form Bio was just the first of the company’s spinout opportunities.

Colossal created the software behind Form Bio to run its own labs, then sold it to other labs in biotech and academia. Lamm, who sits on its board, said Form Bio is working with other companies on projects such as using machine learning to design drugs, with the opportunity for it to create joint ventures and share revenues.

Lamm thinks Colossal can partner with pharma and biotech on using new multiplex editing tools it is developing in humans. Treatments using gene editing techniques like Crispr are being developed for diseases such as sickle cell disease that are caused by a single faulty gene. Multiplex editing could allow the treatment of conditions caused by multiple genes.

Eriona Hysolli, head of biological sciences at Colossal, listed some of the possibilities of gene editing: “With multiplex editing, can you actually target the diseased cells or tissue? Can you target multiple genes at the same time, not just monogenic diseases, but multigenic diseases like diabetes or Alzheimer’s?”

Lamm hopes the 17-person team working on artificial wombs will create technology that could be licensed or spun out into another company to help human reproduction. “It is kind of like Mars. Lots of people are working on Mars and think they will eventually get there. I feel very similar on the ex-utero development side.”

In the meantime, Colossal is working on ways to publicise the project further and earn revenue from media partnerships.

Lamm said every large entertainment studio had contacted Colossal to express interest in filming their work. Several of Colossal’s investors have a background in media, including Tull, who is the former chair and chief executive of Legendary Entertainment.

“We want to educate and inspire by creating mammoths or dodos,” Lamm said.

There may be opportunities to go and look at animals created by Colossal, but James said the company had not decided how much access to give to the public.

He resisted comparisons to Jurassic Park. “That association isn’t my favourite because I think we’re doing this for purposes other than vanity. And also I think we’re probably taking a few more ethical considerations along the way,” he said.

Church, however, thinks the film did scientists a favour by encouraging people to think about what can go wrong. “It vaccinates us against particular scenarios. It is unlikely we’re going to make the exact mistakes they made in Jurassic Park,” he said. “First of all, I’m not in a big rush to do hyper carnivores.”

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Hannah Kuchler