NHS capital investment cuts leave England’s hospitals crumbling

In the basement pharmacy at St Mary’s Hospital in London, part of the world-renowned Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, senior pharmacist Michele Garwood has placed plastic trays beneath the ceiling in an attempt to protect her stock of medicines from regular flooding.

Elsewhere, on Albert ward, one of five lavatories has been out of use for three months after a hole opened up in the floor, exposing it to the car park below, and rotted floor joists in patient bays, temporarily taped over, represent a constant trip hazard.

We “still provide the best care we can” but some patients are so horrified by their surroundings that they discharge themselves, said matron Marta Calvo Hernandez.

St Mary’s is one example of how a longstanding lack of capital spending is being felt across the NHS. The service is struggling with an accumulated maintenance backlog estimated to be worth more than £10bn, the highest since records began.

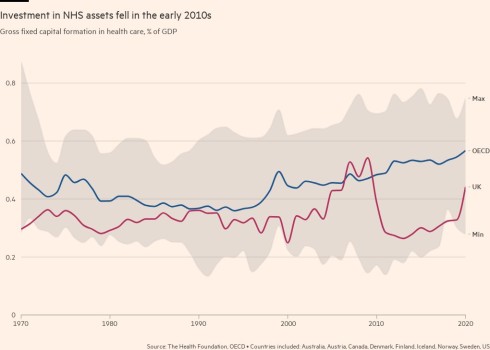

Stephen Rocks, an economist with the Health Foundation, a research organisation, said there had been “a very sustained under-investment in capital” over the austerity years of the 2010s, which had “left the NHS with insufficient capital investment to deliver the care patients need”.

Rocks suggested this was part of the reason that a growth in staffing levels in the health service did not seem to have translated into a corresponding increase in activity.

“We’ve seen a ‘capital shallowing’, with less capital per worker, and that does have a very direct read across to productivity,” he said.

Despite the evident dilapidation at St. Mary’s, where more than half the buildings are older than the NHS itself, it is not a priority in the government’s New Hospital Programme. The scheme, a legacy of Boris Johnson’s time in office, aims to construct or expand 40 hospitals by 2030, backed by about £20bn of capital funding.

The cost of St Mary’s rebuild is estimated to total £2.2bn — although this would be offset by selling land owned by the trust, reducing the contribution from the government to between £1.2-1.7bn.

The strategic case for the work was approved in 2021, but after five other hospitals were found to have deteriorating concrete roofs that posed a severe safety risk, St Mary’s was told it was no longer at the front of the queue.

Surveying his crumbling domain, chief executive Tim Orchard, who is also a consultant gastroenterologist, cannot hide his incredulity that so many other projects can be deemed more pressing than his own.

“I would find it very difficult to imagine worse estate than this,” he said.

Past disasters have included “a big problem with sewage coming out of the drains in our outpatient department” and “a very considerable electrical and flooding issue” in a relatively new part of the estate that meant “having to close down all elective work in one of the buildings for three weeks”, he added.

Heath department insiders said St Mary’s remained part of the New Hospital Programme and suggested rebuilding would start before 2030, although they acknowledged that work would continue beyond that date.

The St Mary’s site includes historic buildings such as converted stables, once used by the nearby Great Western Railway. But the charm escapes staff who must provide outpatient and day treatment from premises dating back to the Victorian era.

Deirdra Orteu, a former nurse who is one of the leaders of the trust’s redevelopment programme, pointed out a ward that has been permanently closed due to a structural problem with its ceiling that is considered simply too expensive to repair.

Orchard stressed that the care patients receive at his trust is still first-rate — its maternity unit has recently been rated outstanding by the Care Quality Commission, the health service’s inspectorate, despite operating from a building opened in 1863 — but all too often staff are delivering it despite their surroundings.

All of this has implications for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s pledge that waiting lists for non-urgent care, currently standing at 7.6mn, should be falling by the time of the general election expected next year.

Orchard said the hospital has still managed to achieve steep cuts in long waits for treatment and if not for the impact of NHS strikes, he believed waiting lists would this year have started to plateau and then fall. But he acknowledged that “there’s absolutely no doubt that is much harder if you’re doing it in a situation where you cannot rely on your estate”.

Some of the buildings have received attention in recent years. Backed by about £920,000 in investment, the hospital’s same-day emergency care department is a national pioneer where patients receive treatment such as transfusions and MRI scans, relieving pressure on the hospital’s endlessly overstretched A&E department.

St Mary’s is also at the centre of Paddington Life Sciences, a growing cluster that links clinicians with academic, community, pharmaceutical and technology organisations that have offices close to the hospital. The trust hopes to increase collaboration and attract funding via clinical trials and other healthcare innovations.

The presence of the organisations “can demonstrate social value for our community”, argued Orchard, adding they can give an economic boost to a district with high health inequalities. He pointed out that there is a 13-year difference in life expectancy between the hospital’s immediate neighbourhood and the area around Hyde Park, a 10-minute walk away.

But visionary plans cannot obviate the desperate and immediate need to provide better facilities for patients and his workforce.

Orchard fears the hospital may not receive substantive funding until 2030 and, given the scale of the work required, it could be another six or seven years before it is completed.

He said this would risk healthcare provision “in one of the most deprived parts of west London”, as well as a for patients from around the country who come to be treated for some rare infectious diseases and cancers.

He added that after so many years, patients as well as staff have got used to the conditions in which they operate, but “the danger is that you start colluding in the idea that this is how it is, how it’s always been and how it always will be”.

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Sarah Neville