Transplanted pig kidneys provide ‘life-sustaining’ functions in human for first time

Genetically modified pig kidneys have for the first time provided “life-sustaining renal function” for a week after transplantation into a human recipient, surgeons leading the successful operation have said.

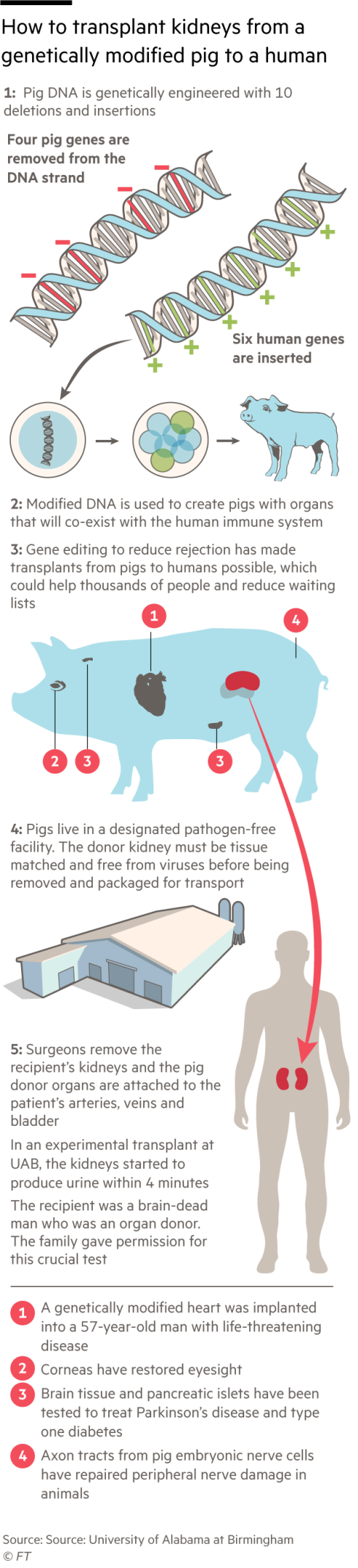

The results from the study advance the promise of xenotransplantation — using organs from animals genetically engineered to prevent rejection — as a therapy to address the severe worldwide shortage of kidneys from human donors. In the US almost 5,000 patients a year die while waiting for a transplant.

The unnamed recipient of the pig kidneys was a 52-year-old “decedent” man who had been left brain-dead by an accident. He had asked his family to donate his body for research after his death. Results were published in the journal JAMA Surgery.

“The [pig] kidneys functioned remarkably over the course of this seven-day study using current standard immunotherapy drugs,” said Jayme Locke, leader of the University of Alabama transplant team. The surgeons hope the safety and scientific information gathered from the study will boost their efforts to secure regulatory approval for a Phase I clinical trial in living humans.

The Alabama team carried out a similar operation last year on a 57-year-old man who was also left brain-dead by a motorbike accident. Although the pig kidneys produced urine and were not rejected in that experiment, they failed to carry out a key renal function — clearing creatinine, a waste product made by the muscles. The researchers had to end the experiment early.

In both studies the participants had their own failing kidneys removed and replaced with organs from pigs with 10 genetic modifications that reduce the risk of rejection by the recipient’s immune system and help the organ grow in a human body. Four porcine genes were inactivated and six human genes added.

In the latest study the transplanted pig kidneys produced healthy quantities of urine and were able to filter creatinine from the blood. Biopsies showed no sign of damage to the renal cells and blood vessels. The animals were developed for xenotransplants by Revivicor, a Maryland subsidiary of biotechnology group United Therapeutics, and grown in a pathogen-free facility in Alabama.

Roger Lord, an expert on immunology and transplant biology at Australian Catholic University, who was not involved in the study, said it “provides important preliminary evidence that genetically modified kidneys can function normally following xenotransplantation and offers hope to those on waiting lists for kidney transplantation”.

The study stopped after seven days and the recipient’s life support was switched off, as specified in advance by the university’s institutional review board and ethics committee, but the evidence suggested the kidneys could have continued to function healthily for much longer, said Locke.

“We have since received permission to extend studies out to 30 days, if the families decide that is appropriate,” she added.

Xenotransplants have been a focus of medical research for several decades. But advances in genetics and immunology have only recently brought the technology to a point at which regulators will consider its use for clinical practice.

Last year the first man to receive a pig’s heart transplant died two months after the operation at the University of Maryland Medical Center. A subsequent autopsy found that his new heart showed no signs of rejection but he had succumbed to “heart failure caused by complex factors”.

Locke believes that the US regulator, the Food and Drug Administration, should permit a Phase 1 clinical trial of kidney xenotransplants into living recipients to begin as soon as possible without insisting on further data from studies with monkeys.

“I don’t think the non-human primate model is ever going to provide the answers we need for FDA applications,” she said. “I had hoped that the FDA would approve a Phase 1 trial this year but now I don’t think that will happen.”

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Clive Cookson