Eli Lilly achieves hard-won success with Alzheimer’s and obesity drugs

US drugmaker Eli Lilly is riding a wave of investor optimism and media hype about new treatments for two of the biggest public health problems: obesity and Alzheimer’s.

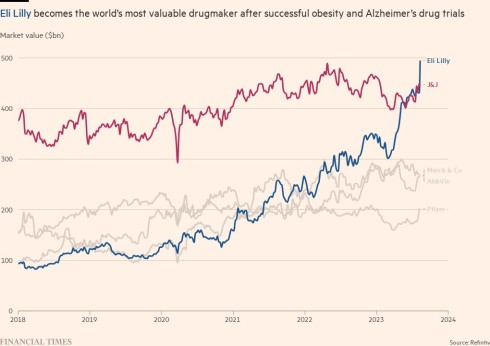

Scientific breakthroughs for both diseases have caused its shares to surge 75 per cent to a record high over the past 12 months. This week it leapfrogged Johnson & Johnson and UnitedHealth to become the world’s most valuable drugmaker and healthcare company by market capitalisation.

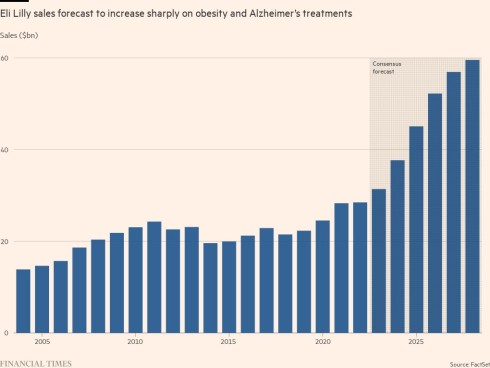

Chief scientific and medical officer Daniel Skovronsky told the Financial Times that Lilly was planning to launch more than 20 new drugs over the next decade to sustain its growth and that it wants to become the first trillion dollar healthcare company.

As well as Alzheimer’s disease and obesity, it also wants to expand its drug pipeline in oncology and develop treatments for underserved illnesses such as chronic pain, he said.

“It is not enough just to have good drugs. Let’s have some great ones that change medical history forever,” said Skovronsky, who spearheaded Lilly’s research and development efforts to develop the obesity and Alzheimer’s drugs.

“The fact that there’s never been a trillion dollar healthcare company. That’s a little surprising. There are few things I can think of that are more important to invest in . . . I hope we can meet this goal,” he said.

Lilly notched up a big win last month when it published the results of a late-stage trial showing its Alzheimer’s treatment donanemab significantly slowed memory loss and cognitive decline. It expects to receive regulatory approval later this year and carve up a market that could be worth $14bn a year by 2030 with rivals Eisai and Biogen.

The second drug that has lit a fire under investors is diabetes and weight loss treatment Mounjaro.

US regulators approved it to treat diabetes last year. Then in April, Lilly revealed a large trial had found it also cut body weight by 16 per cent on average over 17 months. Regulators are expected to approve it as an obesity treatment in the autumn. BMO Capital Markets forecasts this market could be worth $100bn a year by the middle of the next decade.

Mounjaro is one of a new class of drugs known as GLP-1 agonists that work by lowering blood sugar levels after eating and suppressing appetite.

“Lilly has really struck oil with its obesity franchise,” said Colin Bristow, an analyst at UBS, who forecasts annual sales for Mounjaro of $35bn by 2035.

“They have found what looks to be a best-in-class asset and a best-in-class pipeline in one of the largest untapped markets in therapeutics.”

Lilly faces competition from Danish rival Novo Nordisk, maker of diabetes and weight loss drugs Ozempic and Wegovy.

But late-stage trials showed that when Mounjaro was used to treat diabetes, it caused more significant weight loss than Wegovy, although there have not been any direct comparison trials. In June, Lilly published interim trial results for a drug called retatrutide, showing it helped people lose a quarter of their body weight in 48 weeks — the highest reduction yet for an obesity drug.

Lilly’s success has been hard won. Back in July 2016 when David Ricks was named successor to then chief executive John Lechleiter it was rebuilding after a plunge in revenues caused by the expiry of patents on several top-selling drugs. A few months later, its Alzheimer’s drug Solanezumab failed a pivotal clinical trial and US regulators delayed approval of an experimental therapy for rheumatoid arthritis.

The company cut 485 jobs, mainly from its Alzheimer’s division, but did not give up on its goal of developing the first treatment for the disease. Lilly raised $1.7bn in cash by spinning off a 20 per cent stake in its animal health unit, ploughed money into R&D and focused its efforts on five therapeutic areas: diabetes and obesity, neurodegeneration, cancer, immunology and pain management.

“It was tough,” said Skovronsky, adding that some in the company had wanted to drop Lilly’s two decade-long effort to develop an Alzheimer’s drug and focus on other areas.

Lilly also faced frequent external criticism from investors and elsewhere about why it invested so much in R&D, typically about a quarter of its annual revenues, he said.

But following discussions with Ricks and the board a decision was made to continue Alzheimer’s research, building on Solanezumab.

Skovronsky said Lilly’s commitment to R&D and its focus on areas of long-term internal expertise have been critical for its success. He added that the company’s relatively remote location in Indiana means many employees stay for long periods, insulating it from certain external pressures.

“We have some advantages in terms of being able to pursue sometimes unpopular ideas for long periods of time. And I think that’s important, because science takes a while to figure out. We have watched so many competitors jump from area to area. One day they are in Alzheimer’s and then next day they are out and on to something else.”

Evan Seigerman, an analyst at BMO Capital Markets, said Ricks has followed a strategy of “underpromising and overdelivering” as chief executive and avoiding some of the pitfalls that have affected rivals.

“He was able to really focus on the long-term growth of the company. And what is remarkable to me is that [Mounjaro] and donanemab are all kind of homegrown assets. These are things they really built themselves.”

Lilly has avoided the transformational but risky megamergers that became a feature of the pharmaceutical industry over the past two decades until US regulators started intervening more recently. Instead, it has prioritised internal R&D and smaller acquisitions to add to its drug pipeline.

“Lilly hasn’t been one of those really big deal junkies,” said Les Funtleyder, a healthcare portfolio manager at E Squared Capital Management, which owns Lilly shares.

He said Lilly had benefited from its strong research culture and breakthroughs in the two biggest untapped pharmaceutical markets. In contrast, Pfizer had invested a lot in internal R&D without managing to bring many blockbuster drugs to market.

“Lilly has been a bit lucky as it turned out their diabetes drugs happen to be great for weight loss and their Alzheimer’s drug is on course to be approved despite some questions over efficacy and safety. But they clearly have an R&D engine that works, so they make their own luck,” said Funtleyder.

Despite its recent successes, Lilly faces challenges in delivering on the high expectations of investors, given its shares trade at 56 times forecast earnings in 2023. Some doctors have warned uptake of its Alzheimer’s drug could be slower than expected because of concerns about side-effects that can include swelling and bleeding of the brain.

For Mounjaro, analysts have set very high annual peak sales forecasts — ranging from $35bn from UBS to $70bn by Jefferies — before the drug has even been approved by regulators to treat obesity. Meeting these will be difficult, particularly since Lilly and Novo Nordisk are struggling with manufacturing capacity, causing shortages of Mounjaro, Ozempic and Wegovy.

There is also no guarantee that public and private insurers will fund the $1,000 a month cost of Mounjaro for all patients, due to the huge costs of treating a disease that affects about 40 per cent of Americans. Or that they will agree to maintain coverage for a patient’s entire lifetime — studies have shown that weight is usually regained after treatment is stopped.

Skovronsky said a study published this week by Novo, which showed that Wegovy cut the risk of heart attacks and strokes by 20 per cent should help persuade insurers to cover the drugs.

“Now we have the data to show . . . this is not an aesthetic problem. It’s a medical problem,” he said.

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Jamie Smyth