Third of England’s healthcare facilities at risk from heatwaves by 2050

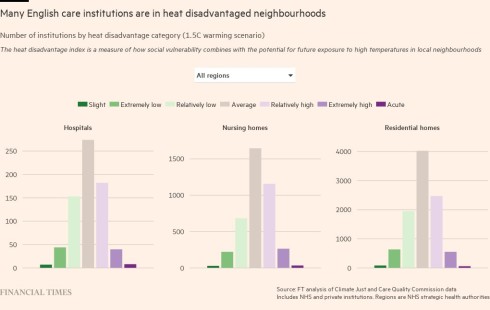

A third of hospitals, nursing homes and care homes in England are situated in areas that climate scientists predict will be at high risk from hotter summers by the 2050s, with that figure rising to nearly three quarters in London, according to research by the Financial Times.

Global warming will mean almost 5,000 of the 14,531 healthcare facilities will be in areas of high or acute levels of heat “disadvantage” by the middle of the century, an FT analysis of data from the Care Quality Commission and the Climate Just research group found.

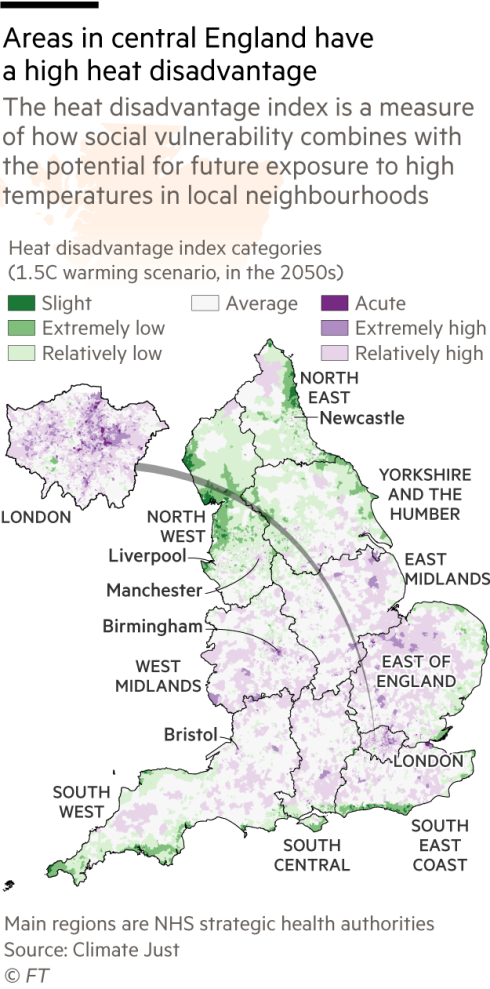

The analysis took into account a region’s vulnerability — using factors including the local population’s age, health and income levels — and the impact on each area if the world remains on course to warm by at least 1.5C by the end of the century, compared with pre-industrial levels.

It found that London’s facilities would be at particular risk as a result of factors including higher levels of homelessness in the capital, a more built up urban environment that gets hotter than surrounding green spaces and the city’s location in the south east of England.

The elderly, ill and very young are especially sensitive to overheating, but most NHS hospitals and privately run care homes have not been designed with high temperatures in mind — and the risks are growing.

In July, the Met Office warned that a year like 2022 — when temperature records were broken as parts of England exceeded 40C last summer — would be considered “average” by 2060 if global warming continues.

Earlier this year, the Climate Change Committee, the government’s independent climate advisers, warned that progress on preparing healthcare facilities for hotter summers was far too slow. There was “no policy to manage overheating risks in existing health and social care buildings”, it said.

It also noted that while it had been able to identify incidents of “overheating” in hospitals, there was no data available for other healthcare settings. In terms of government policymaking aimed at future-proofing cities from a warming climate, the CCC concluded: “There remains a gap for joined-up strategy for managing urban heat overall.”

The heatwave last year led to more than 2,800 deaths among those aged 65 and over in England alone, according to official data. Another data set showed that between June and August 2022, deaths in hospitals in England and Wales were 6 per cent above average on unusually hot days, while in care homes that figure was 9 per cent above average.

In warm weather, the human body has to work harder to keep cool. Hot conditions can exacerbate cardiovascular and respiratory conditions and increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

“Last year was a bit of a turning point,” said Mike Padgham, managing director at Saint Cecilia’s Care Group, adding that he was “watching in horror” the heatwaves currently gripping much of Europe.

“We don’t have enough resources of our own to convert the buildings to be more heat friendly,” said Padgham, whose care homes are in and around Scarborough on the north-east coast. “We’re looking after some pretty vulnerable people so they’re going to be at risk.”

Adeline Siffert, from the British Red Cross, said the emergency services were “stretched to their limit” during last year’s heatwave, highlighting the systemic risks of not preparing for hotter temperatures.

Evidence given in recent weeks to a review commissioned by London mayor Sadiq Khan into how to make the capital “climate ready” included warnings from senior NHS staff that the estate was “not fit for purpose”.

And it is not just the direct risk to patients and care home residents posed by higher temperatures. In the middle of the heatwave last year, two data centres that hosted IT systems for London’s Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital Trust overheated and failed, significantly disrupting patient care.

Part of the problem is that most buildings in England are not designed to cope with extreme temperatures. The government published new regulations last year designed to prevent overheating in new residential buildings in England, including care homes, but they do not cover existing or non-residential buildings.

Solutions such as insulation and installing air conditioning are expensive, but there are cheaper ways to keep buildings cool, such as painting roofs white or planting trees to create shade.

Dr Latifa Patel, the British Medical Association chief officer, said the sharp increase in the number of overheating incidents in hospitals was “incredibly concerning” and investment was urgently needed “to modernise heating and ventilation systems”.

Although efforts so far have been disjointed, there are signs of progress, starting with a growing awareness of heat as a problem.

The NHS net zero building standard, published this year, requires new buildings, and upgrades to existing facilities, to factor in the potential for overheating into designs.

The UK Health Security Agency’ has set up a Centre for Climate and Health Security, which is developing a series of metrics to help healthcare professionals track and analyse the effects of climate change. The HSA’s plan for adverse weather states that “all health and social care staff should be prepared for extreme heat”.

But strained healthcare budgets, and the fact that responsibility for preparing hospitals and care homes for a hotter climate is split across different bodies — from the government to NHS England to private care home operators — make addressing the issue even more complicated.

An academic paper published this year emphasised the need for “strategic, long-term planning, prevention and investment” to enable healthcare staff to prepare for heat-related risks, but said that had been “limited by a lack of financial investment in the management of healthcare estates”.

The government said in a statement that patient safety was its “top priority” but noted that NHS trusts were responsible for maintaining their own buildings.

Meanwhile, individual care homes are doing what they can. Alina Verescu, general manager at Signature at Hendon Hall in London, said air conditioning had “become a necessity” during the hottest weeks of the year.

In Scarborough, Padgham said the group’s homes moved residents into the centre of buildings where it was cooler and closed curtains during last summer’s heatwave.

“We can do the easy bits but the most difficult part is air conditioning” and making “physical changes to the homes”, he said, stressing that the social care sector had limited resources.

“We’d like to think the government might provide some financial assistance to homes” to enable adaptations to take place, said Padgham. Last year was a sign that “we need to be planning for [heat] now”.

Data visualisation by Chris Campbell. Additional reporting by Sarah Neville.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Camilla Hodgson