How a squad of MAGA warriors flush with cash turned on each other Then a knock-down, drag-out brawl broke out

Doctor Simone Gold looks like a high school valedictorian. Practical jeans and a cap-sleeve T-shirt. Indoor-kid skin that looks even paler now that she’s in Florida. Gold glitter nail polish applied in an impulsive stab at having a little fun. Her voice has a confident, sped-up cadence that sounds like it should be saying, “Come on guys, we have to focus.” She is 5’8” but looks shorter; she’s 57 years old but appears much younger. Most of all, Simone Gold looks like someone who has never got in trouble. Until the pandemic, she never had.

Gold is staring out the living room windows of her home in Naples, Florida, to stop herself from crying. “For the rest of my life, there’s going to be a question of if I’m a thief,” she says, focusing on the palm trees lining the $3.6mn house purchased for her by America’s Frontline Doctors, the non-profit she founded to fight Covid-related restrictions. “I’m Erin Brockovich. And now you’re telling the world that I stole from the people? My core understanding of who I am is: I do the right thing. So, it’s insanely painful.”

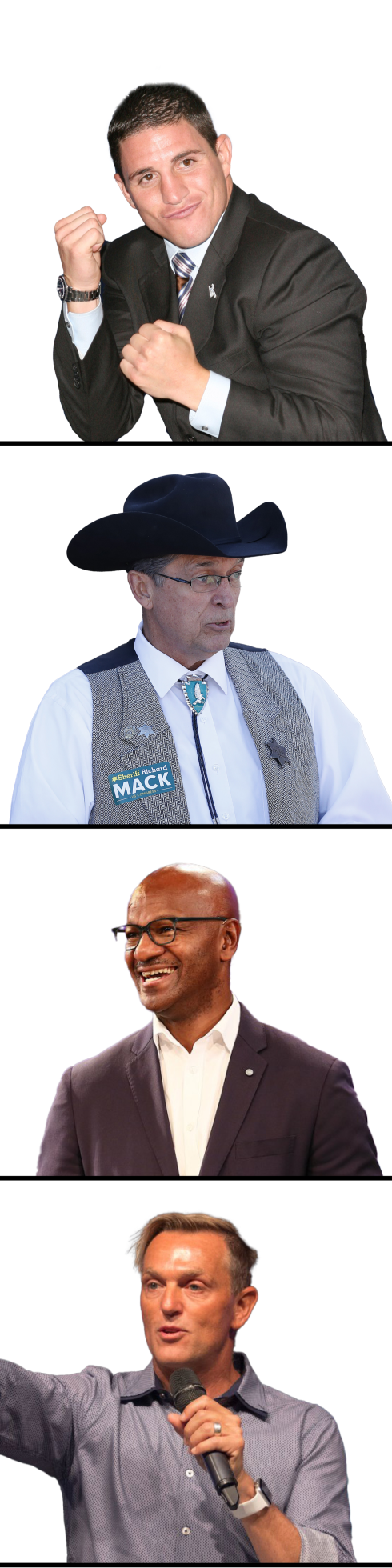

The root of the pain began three years ago, when the emergency room physician, Stanford Law School graduate and Beverly Hills mother took on the medical establishment. Which led to her taking on the government establishment. Which led to her taking on her anti-establishment colleagues at the anti-establishment non-profit she built. While we assembled jigsaw puzzles and tended to sourdough starters, Gold raised millions, met with US representatives, waltzed into the US Capitol on January 6, went to prison for six weeks and, once she got out, sued the reality-show boxer, the former Arizona sheriff and the megachurch pastor she had assembled for the board of America’s Frontline Doctors.

Gold grew up in Hewlett, New York, one of the tony, largely Jewish areas in Long Island known as the Five Towns. Her father, a doctor who survived the Holocaust, made one thing clear to his three kids: they were going to be doctors too. She did it incredibly quickly. After graduating from medical school at the age of 23, Gold headed to Stanford. But when she wasn’t studying the law, she was working as a doctor at an urgent care facility. The only social experience she can recall is going to a campus cafeteria with a classmate named Casey Cooper. When he asked her out to dinner in Palo Alto, she turned him down.

After getting her law degree, Gold specialised in the highly paid field of emergency medicine. Which was gruelling. “I don’t think I’ve ever made decisions based on what made me happy,” she says. Ever on track, in 1999, Gold met a guy who lived in Los Angeles and married him. They had two kids. They got divorced. She moved into a condo within walking distance of Beverly Hills Synagogue, figuring it was the most efficient way to meet a nice Jewish guy.

Then Covid hit. Gold’s initial reaction was different from yours, assuming you’re human. “I was sort of stoked. I’m like, ‘What’s going to happen?’” she says. “And that’s what you’d like in your ER doctor.”

When lockdowns began in California, she became a lot less stoked.

For most of her life, Gold hadn’t been any more political than she was social. She was pro-choice and not pro or anti much else. “I remember distinctly voting for Bill Clinton twice. I may have voted for Gore,” she says. She has trouble remembering who ran against Barack Obama, but she is absolutely sure she voted for whoever it was. Because, as an activist, Obamacare was her Vietnam war. “I hated Obama. You looked at [Obamacare], and it was crap. You didn’t get to keep your doctor. And then the media didn’t say anything about it. So I started to hate the media,” she says, smiling and bobbing her head side to side in a Muppet sort of way that does not at all make me feel hated.

When Donald Trump started to talk about repealing Obamacare and hating the media, she found the first candidate she was ever excited about. He didn’t let her down once he was in office. To protest against the lockdowns that both Trump and she objected to, Gold posted a video of Cedars-Sinai hospital to show that it wasn’t overrun with patients. In May 2020, she got more than 500 other doctors to sign an open letter to the president claiming lockdowns were going to cause a “mass casualty incident”.

Like many doctors in those early weeks, Gold prescribed her Covid patients hydroxychloroquine, which is a pill often given to people travelling to countries with malaria. Trump was not only talking it up as a cure in press conferences, he was also taking it prophylactically. But in June, after several large studies suggested it was ineffective, the US Food and Drug Administration revoked its emergency authorisation. Sure, Gold’s patients recovered after taking it, but people also recovered from Covid after watching Tiger King.

Gold disagreed and organised a group she called America’s Frontline Doctors, which included an ophthalmologist, a neurologist and a paediatrician, who has prescribed more hydroxychloroquine than any other doctor in America. In July 2020, they travelled to Washington to hold a two-day summit about its effectiveness, during which Gold scored a meeting with vice-president Mike Pence, head of Trump’s coronavirus task force. She also held a press conference on the steps of the Supreme Court which was live-streamed by Breitbart News. Trump retweeted the video and, within eight hours, it had more than 17 million views. By nightfall, Facebook, YouTube and Twitter yanked it for containing misinformation. Several days later, she was a guest on Fox News’s Tucker Carlson Tonight.

Gold was becoming famous. And infamous. Both hospitals she worked for in California stopped allowing her to come to work. I called Gold a few weeks later, wondering how she was coping with exile from the institutions she spent her life grinding to get into. Was she depressed? Regretful? She was confused by my questions. Then she said: “From your position from the left, you think I’m getting attacked. But everyone has been saying, ‘Thank you for coming to save us.’ People want to donate money. It’s been completely uplifting.”

Gold wanted to continue our interview in person, but I was nervous. It was August 2020, the week Boris Johnson delayed easing lockdown restrictions in the UK and the mayor of New York City set up checkpoints to turn away people coming from other states. My wife, son and I hadn’t seen anyone we knew, even outdoors, for more than four months. Gold agreed to meet outside but wouldn’t wear a mask. I considered it, but ultimately was too afraid. Which made her sad. As did the reaction to Covid of her mother, with whom she’d always been close. “She definitely thought I was wrong. Because to accept that I’m right, you have to accept that everyone is lying to you. One of my sons doesn’t accept that I’m right either,” she told me recently. “Because how scary and sad is a world where everyone’s lying to you?”

Gold’s sad about the sacrifices I — and probably you — made during the pandemic. She says this with such sympathy and sincerity that I want her to be right, that the many vaccines I took, the masks, the sheltering in place — it was all a trick. She’s so calm and self-assured, so knowledgeable and good at bedside manner, so happy New Testament over Old, that I almost want to follow her.

A lot of people did. John Strand, a model and singer, was one of them. He sent her $75. “I was making zero and couch surfing for the last 10 years, so that was a lot of money,” Strand says. A month after her speech on the Supreme Court steps, Gold appeared on Joni Lamb’s Christian television network, and viewers sent her more money, which Lamb matched, totalling $137,000. Though Gold says the average donation to her non-profit is $29, she also has received more than $6mn from Timothy Mellon, the 80-year-old grandson of banker and US Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon.

Pretty soon, her non-profit was taking in so much money that Gold hired a press team to disseminate theories about vaccine side-effects (all of which are disputed by mainstream scientists) to the group’s more than one million subscribers. She got lawyers to sue the government over vaccine mandates. She set up a website that offered $90 telemedicine appointments to get hydroxychloroquine prescriptions and, later, Ivermectin, an anti-parasite drug that anti-vaxxers tout as a Covid cure. Most of all, Gold spoke. She travelled around the country to deliver a message of medical freedom. Her speeches had the euphoric passion of a 1960s hippie, only her version of nudity was stripping off your mask.

At events, she met far-right activists who introduced her to all kinds of ideas she’d never heard about the government. When I went to her house in Naples, Florida, this March, she Zoomed in as a guest on the ThriveTime Show, a podcast hosted by conservative author Clay Clark. Her fellow panellists were former Trump national security adviser General Michael Flynn and a guy who runs Beverly Hills Precious Metals. As Clark quoted the bible to explain that gold is the only God-approved currency and that the Covid vaccine contained a tracking cryptocurrency that contains the mark of the Beast, Gold put herself on mute and said: “Your story should be about how a nice Jewish girl got herself in this situation.”

In October 2020, a few weeks before the presidential election and days after Trump got Covid, Gold spoke at the American Priorities Conference, also known as AMPfest. The four-day event was held at Trump’s Miami resort and featured anti-vaccine crusader and 2024 Democratic presidential candidate Robert Kennedy Jr; Florida representative Matt Gaetz, who voted to nominate Trump for a Nobel Peace Prize; and political consultant Roger Stone, who was pardoned by Trump days before he was to go to prison for obstruction of justice, witness tampering and multiple counts of lying to Congress.

Joey Gilbert, a Reno, Nevada, attorney, was also there. One of the first things you see in the Reno-Tahoe International Airport is a huge ad on the wall featuring a man in a suit and tie, with short-cropped dark hair, holding two fists to the camera and looking tougher than Reno, the city in Nevada that Americans escape to when Las Vegas isn’t an option. In the ad, Joey Gilbert Law offers to handle all your drunk driving charges, personal injury, divorce and constitutional law needs.

Gilbert, 47, was a college boxer at the University of Nevada. In 2004, while he was getting a law degree, he was cast on the NBC reality show The Contender, hosted by Sylvester Stallone and Sugar Ray Leonard. He then amassed a 20-3-1 pro record as a middleweight, though he missed 13 months after being suspended for steroids. (Gilbert denies using steroids.) As I waited to meet him at his office in March, I was nervous to confess something. Gilbert entered, wearing a hoodie and two beaded bracelets his daughter made him that read “dad” and “boxer boy”. He offered to shake my hand, and I paused, thinking if this were anyone else, I would have rescheduled.

A few days earlier, my son had got Covid. By the time I got to Reno, I was pretty sure I was developing symptoms. Finally, prepared to get kicked out, I came clean.

“I don’t do Covid,” he said, shaking my hand. Then he gestured towards a box behind his chair. “I got some hydroxychloroquine. Knock it out in two hours.”

Like Gold, Gilbert wasn’t politically active before the pandemic, though he too liked Trump. Then in March 2020, Gilbert’s father, a doctor who spent most of his career in the military, got sick. “This guy is a three-times deployed combat trauma surgeon. A marine. I’ve never seen him sick. That generation — he’s 72 — everything is like, ‘Pain doesn’t hurt.’” Gilbert had read that hydroxychloroquine was being used in South Korea, and he got his dad to call in a prescription. After being in bed for most of two days, he recovered. So Gilbert filed a petition asking the governor of Nevada to authorise the drug. When that didn’t work, he filed a lawsuit. Over the next year and a half, he filed lawsuits to open churches during lockdown, let kids go back to school, end mask requirements and rescind the vaccination requirement for university students.

Before Gilbert went on stage to give his speech at AMPfest 2020, someone asked him if he wanted to meet Dr Simone Gold. Over the preceding few months, she had become a hero of his and the two hit it off. Gold asked him to become involved in America’s Frontline Doctors. “I was looking for somebody who would fight back. And Joey has that in spades,” she says, striking the pose from his ads.

In autumn 2020, Gold accepted an offer from Strand, the model who’d donated to her non-profit, to speak at a protest he was helping organise. Strand, 35, who can be seen on the cover of the romance novel Howl for It, had just returned from a year and a half working in Asia when lockdown started. “I needed to completely reassess my career, my life,” he says. He became an activist. “I was like, you can’t just lock a city down. And if it does happen, something very dark is happening that has nothing to do with the virus. It was clear they were inciting a panic.”

Gold liked Strand right away. He wasn’t the Jew she was looking for, having been a life-long Christian evangelical. But he was hot. She hired him to work as her scheduler and security guard. When she asked him out later, he turned her down. Then Gold asked again. “I thought, ‘Well why not?’ The whole world had shut down,” Strand says. “My circle of friends was rapidly shrinking. I had come out publicly politically. I went from being everyone’s favourite male-model friend, and suddenly I had a bunch of enemies.” For their first date, they spent the day working in Gold’s apartment, Strand put on some Death Cab for Cutie and they ate dinner. “We didn’t even kiss,” Strand says. “We waited until the second day. It was very old fashioned.”

Then Gold and Gilbert were invited to speak at a rally for “health freedom” in Washington. It was scheduled for 1pm on January 6 2021.

Washington was teeming with angry conservatives. Gold, accompanied by Strand, went to hear Trump speak and then headed off to their own rally just a few blocks from the US Capitol. No one was there. People were following Trump’s call to march to the Capitol.

When they got there, Gilbert and his father followed the crowd up the steps of the building. People ahead of them started pushing past the guards. They watched for a while. “These three buses pull up, and people start getting off in tactical gear with Trump outfits running towards the front. You knew it was time to get out of there,” Gilbert says. He and his dad turned around.

Gold also approached the Capitol with Strand, but she didn’t react the way Gilbert did. She was stoked. She followed the crowd through the back doors into the rotunda, then climbed on the base of a statue of President Dwight Eisenhower. She was flanked by Strand, who was in sunglasses, a leather jacket and fingerless gloves, as if he were going to moonwalk Trump back into office. Holding a bullhorn, Gold delivered the speech she’d intended to give earlier. The crowd, however, was less interested in listening than stealing stuff, breaking stuff and smearing faeces on stuff. That night, she went out to dinner with friends, who worried she’d be arrested. Gold assured them that she was a lawyer and that she hadn’t broken any laws.

Twelve days later, Gold and Strand were working on her sofa in her apartment in Beverly Hills when she heard: “FBI! FBI! FBI!” That can’t be real, she thought. The FBI would call first. When she stood up to open the door, agents broke through with a battering ram. The FBI didn’t let Gold collect her phone or wallet before taking her to jail. “I cried a little bit in the car. Not for me. I was weeping for our nation,” she says. She was sure the show of force was an attempt to suppress her political opinions. “The things you think are solid may not be. What are the odds I ever thought I was ever going to be in a maximum-security federal penitentiary? This was like going to Mars. It’s like Elon Musk calling me up, ‘Hey, you want to go on the spacecraft?’ That would’ve been more likely. I’m an important person. People think I’m smart. I might be called to do that.”

She spent the night in a holding cell and was released in downtown LA the next day. She only had two numbers memorised, and one of them was for Strand, who was also in jail. So she called her son, who ordered her an Uber.

Four days later, authorities released Strand. Which led to what is, perhaps, the closest thing the insurrection has to a meet-cute. Strand, who was put under house arrest, was going to give the police the address of a friend whose place he’d been staying at. But that meant he couldn’t be with Gold. “So we decided to have him move into my apartment,” she says. “I needed him to work.” The couple that gets raided by the FBI together, stays together.

Gold’s arrest turned out to be a huge fundraiser. By the end of last year, America’s Frontline Doctors had brought in more than $25mn. Strand set up his own website for donations to his legal defence. It displayed a modelling headshot and the tagline “From Gucci to Guilty”, a catchy, if poorly thought-through, turn of phrase.

Now that the federal government was prosecuting her, Gold was worried about the future of America’s Frontline Doctors. In March 2021, she asked Gilbert to join the non-profit’s board of directors. Nine months later, she added Pastor Jurgen Matthesius, a blond, mohawked Australian who runs a 10,000-member evangelical church in San Diego, and Richard Mack, a 70-year-old former Arizona sheriff, who once served on the board of the Oath Keepers, a far-right militia, and who currently runs the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, which believes that sheriffs — not the courts — should decide which laws are constitutional.

The board’s first decisions were financial. “We took in more money than I felt we could responsibly spend,” Gold says. “I had three choices. Keep it in the bank. That’s going up with Biden inflation. Spend it. Or put it somewhere safe.” She decided on real estate, but she wasn’t going to invest in liberal California any more. America’s Frontline Doctors bought the house in Naples, and she and Strand moved in. The non-profit also paid for a Mercedes-Benz van, Hyundai Genesis and GMC Denali, provided $5,000 a month in housekeeping fees and $20,000 a month for security. This was in addition to Gold’s annual salary of $600,000.

Gold named Gilbert chair of the board. Which was a lot of responsibility for a dad who not only had a full-time job as a lawyer, but also was running in the Republican primary for governor of Nevada. Gilbert eventually received the Nevada Republican party’s endorsement, over former Senator Dean Heller and the Trump-endorsed Clark County sheriff, Joe Lombardo.

Gold was busy preparing for her trial, running America’s Frontline Doctors’ day-to-day operations, getting her medical licence in Florida and embarking on an RV trip through Arizona, Texas and Florida called “The Uncensored Truth Tour” (VIP tickets cost $1,000). She was also launching her new for-profit business idea: GoldCare Health & Wellness, a network of clinics that would enlist the anti-Covid-vaccine doctors she’d met over the years. It wouldn’t accept insurance or take money from pharmaceutical companies. And it would have its own medical advisory council as an alternative to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Since the medical system was corrupt, she was going to create a new one.

Gold wanted America’s Frontline Doctors to launch GoldCare, but the board thought combining a non-profit with a for-profit was a bad idea in the sense that it’s not legal. In February, Gold told the board she would be leaving America’s Frontline Doctors and asked for $1.5mn in seed money to start her company. She also wanted to continue to take a salary of $50,000 a month from the non-profit, calling it a consulting fee. The board wanted to consider those suggestions. They say she quit unconditionally during that meeting; Gold says she only agreed to leave if they offered a payout.

Meanwhile, Gold decided to plead guilty, figuring that the misdemeanour charge wouldn’t carry any jail time. (It also meant she wouldn’t lose her medical or law licences.) This caused some tension in her relationship. “My lawyers said, you can’t tell John until we tell the judge, because we were co-defendants. So he’s in one room; I’m in another room. We’re on the Zoom and he’s like, ‘You’re taking the plea?’ He was very disappointed. Going to prison for 20 years is not a factor that John takes as seriously as you, me and 99.99 per cent of humanity. He thinks it’s all up to God.”

When it came to sentencing, Gold’s lawyer told her she got lucky. Her case had been assigned to a solid, smart judge, Christopher Cooper. Gold looked him up. It was Casey Cooper, the guy who asked her out when they were in law school. “I thought, maybe he’s going to be nice to me because of that, and also maybe he has loyalty to Stanford,” she says.

At the trial, Judge Cooper didn’t mention any fond memories of Gold. He sentenced her to 60 days in prison and a $9,500 fine for trespassing, saying, “I find it unseemly that your organisation is raising hundreds of thousands of dollars for its operations, including your salary, based on your participation in January 6.” Though he did wish her luck and hoped that she put this all behind her. So that was nice.

Gold worried the government might seize some of America’s Frontline Doctors’ assets. She had come to trust and rely on Gilbert more than anyone in her organisation, so she emptied $1.1mn from an account she controlled and had him put it in a new holding account. A second account that she used for payroll, with $1.2mn, stayed in the non-profit’s name.

About a week after Gold’s sentencing, Gilbert dropped her off at the Federal Detention Center in Miami. Then he drove to the house in Naples. Two days later, he called a meeting with the 80 or so people involved with the non-profit. “I say, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, there’s a new sheriff in town. As of 5pm today, all your credit cards have been shut off,’” he recalls.

Gilbert claims he discovered spending that could lead to legal trouble. He says Gold was racking up an additional $50,000 a month in expenses on top of her salary, rent-free house and cars. Because the government put her on a no-fly list after she was arrested, she took private planes; one trip cost more than $100,000, Gilbert says. He adds that Strand racked up as much as $17,000 a month on a credit card. “He’s getting cologne. He’s getting food. He’s getting vitamins. He’s buying bubbly water,” Gilbert says. There was also a foundation credit card in Gold’s son’s name.

Gilbert asked Wagenmaker & Oberly, a law firm specialising in non-profits, to assess the spending. “Their memo lists what they refer to as ‘excess benefit transactions’ and personal inurement to the likes of which they’ve never seen,” Gilbert says. He suspended Strand but kept paying him $10,000 a month as communications director. When Strand started using a different card issued to the organisation, Gilbert fired him. Gilbert says he tried to talk to his friend and culture war compatriot, but he couldn’t get through to Gold. “She can’t understand, ‘That’s not your million bucks. I understand you raised the money, but you did it for a public entity. It’s the people’s money. It’s not yours,’” he says. “She can’t understand that in her brain.”

Gold and Strand deny there was any improper spending. Strand says he was putting video equipment for the organisation on his card, hence the high-dollar amounts; Gold says her son was booking cheaper travel for people and the Wagenmaker assessment isn’t a report, just a list of credit card transactions. “I have no trouble seeing . . . the money belongs to the people, not to Simone Gold,” she says. Gold defends her salary and benefits by noting all the money she raised. “I had earned $17mn in the first 18 months. And $330,000 is what I’d taken up until that point,” she says. “Am I a thief? Yeah, a pretty bad one.”

Because Gold was assigned to a maximum-security prison, she wasn’t allowed many visitors. But Gilbert, a lawyer, could get in. So he flew to see her three times. “She was crying, and it was tough, man. I hated seeing her in there. I would’ve served the time for her,” he says. “That’s how much I respected her and was a friend to her.”

Days before Gold’s trial, Gilbert lost the Republican primary for governor by 11 points. But he hadn’t conceded. Instead, like Trump, Gilbert claimed that the election had been stolen. While Gold was in prison, Gilbert spent a lot of money mounting a challenge to his loss, which a judge eventually dismissed.

Gold was released on September 9 2022. She emerged from prison with a really sweet jailhouse braid and was met by Republican Congressman Louie Gohmert of Texas, who presented her with a folded American flag. She was also given all the mail the prison got sick of delivering to her. There were about 10,000 letters and 30 bibles. Then she flew to Washington for Strand’s trial, where he was found guilty on all five charges.

A week later, Gold called Gilbert. “You know, I really question your business and leadership judgment,” she told him.

“Uh, come again?” Gilbert responded. “Dr Gold, what’s up? Did you just wake up on the wrong side of bed?”

Gold had reviewed the spending under Gilbert, and she was appalled. Andrea Wexelblatt, who had run his gubernatorial campaign, was being paid $12,000 a month to help with communications. Gilbert paid himself $20,000 a month, then temporarily raised it to $25,000. Gold claimed he’d also got America’s Frontline Doctors to pay for first class tickets to his daughter’s tennis match in Tampa. Gilbert disputed this, saying he paid for the flights himself, never had a credit card from the non-profit and was doing the work of five employees.

“This is rich,” Gilbert responded to Gold’s accusations. “You’re paying John Strand ten grand a month, and there’s a bunch of names on this payroll I don’t know. But I could only surmise that they work for GoldCare.” At that point, Gilbert claims Gold said she had an incoming call and hung up. The two haven’t spoken since.

After that, Gilbert named fellow board member Mack to be president of America’s Frontline Doctors, paying him $20,000 a month and tasking him with investigating Gold. Gold told Mack he was investigating the wrong person and should fire Gilbert. “I said give us the proof, and we’ll investigate it. And she said, ‘You don’t need proof, you need to get rid of him,’” says Mack. “I said, ‘Sorry I don’t do that sort of thing.’ Then she started going after me and Pastor [Matthesius] and told us we better quit or she would ruin us.” (Gold says she did not threaten Mack.)

Still, Mack tried to settle the differences between Gold and Gilbert. “I’m a former hostage negotiator,” he says. “I’ve talked a murderer into putting his gun down and coming out of a building. But this one seems more difficult than anything I’ve ever done.”

Gilbert filed a lawsuit in Florida against Gold; Gold filed a lawsuit in Arizona against Gilbert, Mack and Matthesius. “It’s like divorce,” says Gold. “But Joey doesn’t care about the kid.”

Gilbert paid Kevin Jenkins, an anti-vaccine activist in New Jersey, $10,000 a month to create an oversight board to further investigate the organisation. Jenkins had worked with Robert Kennedy Jr to co-produce a film called Medical Racism: The New Apartheid, which warned black people against vaccines. He also accused Hank Aaron, one of the greatest baseball players in history, of getting paid to take the Covid vaccine, before he died of natural causes a few weeks later at age 86. The Center for Countering Digital Hate named Jenkins among the “Disinformation Dozen” who produce “65 per cent of anti-vaccine content” on social media. When I asked Jenkins about this, he told me he was “honoured to be one of the few warriors who fought against the tyranny of our time”.

Some felt they were the target of a smear campaign. I got a text from Wexelblatt, Gilbert’s former campaign manager, who Gold thought was being overpaid to market America’s Frontline Doctors. The message alerted me to a Facebook post, which was initially hard for me to find. Wexelblatt explained that she has to keep creating new Facebook pages because the social network kicks her off for posting misinformation. The post she wanted me to read started, “For the record I’ve never cheated EVER on my husband.” This caught my attention. It ended with: “Many lies are coming out . . . claiming I slept with Joey Gilbert and they have it on tape.” Gilbert says there was nothing improper about their relationship; Gold denies ever saying such things.

Gold attempted to illustrate how much she resents being asked to respond to such accusations, by directing me to my own Wikipedia page. She had edited it to claim that, despite being married, I’m often seen at Starbucks and a restaurant called TAO with a woman who is not my wife and her son, whose “resemblance to Stein is unmistakable”. For the record, I would never frequent Starbucks or TAO.

Like Gold and Gilbert, Wexelblatt hadn’t been particularly political before Covid. She was a bartender in Reno, who was put out of work by lockdowns. She and her husband, who sells commercial real estate, were trying to support their two young sons. She became an activist among her friends, pushing for school reopenings. “They jokingly called me Erin Brockovich,” Wexelblatt told me. After she started working with America’s Frontline Doctors, she got close to Gold, whose youngest son was going to college nearby. “I was kind of an aunt to him. We’d have him over for dinner,” she remembered. “She was a hero. She was a friend. I cried a lot when all of this happened.”

Wexelblatt, who has the high cheekbones and great hair of someone who bartended in a casino town, now runs her own media company making ads for conservative groups. She says the rumours cost her clients and damaged her reputation. “It makes us all sound like a bunch of fricking psychopaths,” she told me. “I have the best attorney in the fricking world, and they said this is like walking through a field of shit. In the end, you’re going to get shit on you. It feels like I’m dealing with people with the maturity of ninth graders.”

In January this year, the judge in the ongoing Simone Gold, MD vs. Joseph “Joey” Gilbert, Jurgen Matthesius and Richard Mack case issued a 20-page statement. The judge was not impressed with either side. Of Gold, he wrote, “The notion that a non-profit company could take donated funds and pay them to a principal of the company to invest in a for-profit business is simply absurd.” As for Gilbert, the judge said his “unauthorised pay increase smacks of self-dealing”. He concluded that Gold had in fact quit the board. But also that America’s Frontline Doctors can’t exist without her. The judge issued no decision, telling the parties to make their way out of the clown car on their own.

Susan Schroeder, a partner at Compensation Advisory Partners, works with non-profits, including Kennedy’s anti-vax group. She thought that Gold’s $600,000-a-year salary was about double the average, but potentially justifiable. Living in the house purchased by the non-profit could also be legitimate; it’s something that private school deans and pastors often do. Severance, she said, is usually twice salary, so the $1.5mn that Gold asked for seemed high if America’s Frontline Doctors was also going to pay her a consulting fee. But not beyond the realm of acceptability.

“Line by line, you can rebut each one as reasonable,” Schroeder said. “But it’s not reasonable when you add it all up. If the IRS gets wind of it . . . these people are going down for sure.” (Gold’s lawyer disputed whether Schroeder had the necessary information to make such a claim.) In comparison, according to the 990 form for the calendar year 2020, Kennedy’s anti-vax organisation brought in more than $40mn in donations, and its highest-paid employee earned $193,929.

Instead of working out a compromise, as the judge demanded, Gilbert and Gold each ran their own version of what they said was the true America’s Frontline Doctors.

Gold oversees hers from Naples, which became the de facto capital of Trumpistan during the pandemic. Right on the Gulf of Mexico, the town has some 20,000 residents, all of whom seem to golf. She can practise medicine here and might take the Florida bar. Trump won the county by more than 25 points in 2016 and 2020. In Naples, Gold found her people, the ones who thank her for saving them.

When I arrive at her house, at the end of a suburban cul-de-sac, Gold greets me at the door. “This is the embezzled mansion,” she says, giving me a tour. It’s less a mansion than a reasonably sized four bedroom with a nice pool in the back. It’s decorated in the exact style of the real estate agent who sold it to her, since Gold took all the furniture used to stage it.

At noon, she runs a fortnightly Zoom meeting with 30 of the people working for her. Nearly all the original America’s Frontline Doctors staff stayed with her, over Gilbert. Strand, her boyfriend, joins from downstairs. She assures them all that enough donations are coming in: “Payroll will continue. No one should be insecure.” Gold spends the entire day doing interviews, juggling responses to her 10 email addresses and telling me that my freedom depends on her success. Gold is the grinder that she’s been since high school, so hyper-focused that she goes all day without eating. If I didn’t offer her a bottle of water from her own fridge, I’m not sure she would have anything to drink.

For dinner, she takes me to Seed to Table, a 74,000-sq-ft supermarket that makes Whole Foods look like an Amazon warehouse. Everything here is proudly organic, local and GMO-free. There are a lot of tables beautifully piled with vegetables and absolutely no aisles where boxed goods would be sold. This is the centre of the Naples resistance, so there are pictures of Joe Biden in the urinals, pizzas sold with “FJB” written in pepperoni and, when owner Alfie Oakes is around, a blue Range Rover in the lot covered with a wrap that reads FJB.

Seed to Table never closed or required masks during the pandemic. Oakes piloted a plane himself to Washington for January 6, though he didn’t go into the Capitol because he felt responsible for the 100 people he encouraged to go.

Shoppers dance to the reggae band playing at the bar upstairs, and the place is packed with diners at various mini restaurants. As we sit down, I notice that slight lowering of ambient volume that happens when a celebrity is around. Then I see Oakes, 55, who also owns the enormous Oakes Farms. He looks like a smiley, tanned Cal Ripken, backslapping his way through the place like he’s the mayor. He eats with us, eager to confer with Gold, who supplied his employees with Ivermectin. He’s signed up to be the first GoldCare client and is about to move his 750 supermarket workers off Blue Cross Blue Shield as a test before transitioning all 4,000.

Strand shows up and orders a steak. Gilbert’s claim about his credit card usage, he says, is absurd. “I’m not out at Saks Fifth Avenue buying clothes,” he says. An America’s Frontline Doctors card isn’t used to pay for the meal; Oakes doesn’t allow a cheque to arrive.

Meanwhile, in the parallel America’s Frontline Doctors universe, Mack, the former hostage negotiator, begged the board to let him make one more attempt. They weren’t convinced it was a good idea. So he went rogue.

He flew to Gold’s house in March. “It was very intense and very emotional. I apologised to her,” he said. She offered severance for both him and Gilbert if they gave back control of the bank accounts and walked away. Which sounded good to him. Four days later, the parallel universe board met over Zoom. They didn’t like Gold’s offer. After Mack left the Zoom meeting, the others stayed on and Jenkins and Gilbert fired him. Matthesius refused to sign the minutes, arguing that taking a board vote after one of the board members left wasn’t appropriate. Gilbert denies any of it was done improperly.

Mack was shocked. Jenkins had become good friends with his family, especially his son. So Mack went rogue again. “I felt like this little coup was all about the money, so I went and transferred $350,000 from a Chase account to a credit union account where they can’t get their filthy little hands on it,” he said. “I wanted the judge to decide where the money should go.”

Afterwards, Jenkins convinced Matthesius and Gilbert to quit the organisation completely. Which wasn’t very hard by that point. “I am very glad I have nothing to do with that mess,” Gilbert recently wrote me in an email.

That nominally left Jenkins in charge of America’s Frontline Doctors. He’s been spending most of his time going after Gold, pursuing complaints against her conduct on various issues, he told me on the phone. After taking a short break to fix a door he accidentally pulled off the hinges while we were speaking, Jenkins said what he really thought: “I think she’s involved with some real deep-state shit.” In the populist vernacular, “deep state” is the second-biggest insult, after “paedophile”.

In March, Jenkins appointed Aaron Lewis, a pastor in Connecticut, chair of the board. But less than two months later, Lewis quit. Jenkins claims he fired him. In his resignation letter, Lewis wrote, “I pray that God will have mercy on anyone who uses an altruistic organisation to enrich themselves personally at the expense of innocent donors.”

Gold is now running her version of the board with Mack. But she’s doing it from her house alone. On June 1, Strand was sentenced to 32 months in prison for obstruction of an official proceeding as well as several misdemeanours. Three years later, many of the people who got together to fight a corrupt system are now accusing each other of building a corrupt system. “We’re worse than the people we were trying to accuse of these other things,” says Mack.

Almost everyone, it seems, has run away, many of them with a lot of money. But the truest of the believers remains. The one that gave up her old life for this new one. Who is continuing to sue Gilbert and vows to pursue Jenkins too. She’s fighting them all from a $3.6mn house in Naples, Florida.

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Joel Stein