The pension deal bonanza remaking the UK’s retirement sector

John Shaw had never heard of a “buyout” or Pension Insurance Corporation until 2021, when his entire pension savings, accrued over four decades at the can-maker Crown, were transferred to the insurer.

Once he understood the details, he was reassured. “It was a big relief to be honest,” says the 71-year-old Shaw, a former health and safety executive. For some years, he had watched as a weakened funding position at his former employer cast doubt on whether it could continue to support the pension scheme.

In 2010, the chasm between the assets and liabilities of the Metal Box Pension Scheme — named for a Crown predecessor company — had reached £700mn. A recovery plan had been agreed, but would take almost three decades to implement.

“I was watching plants closing around Europe, and that was worrying,” he says. Coupled with the deficit, “you get worried about your pension”.

When the scheme transferred to PIC, Shaw became one of more than a million UK savers whose pension benefits are now the responsibility of a life insurance company, rather than a traditional pension fund administered by trustees and backstopped by a sponsor company.

In these deals, insurers take over the scheme liabilities — the obligation to pay pensions to retirees decades into the future — and the assets, typically government bonds and highly rated corporate debt, that have been accrued to finance those pensions.

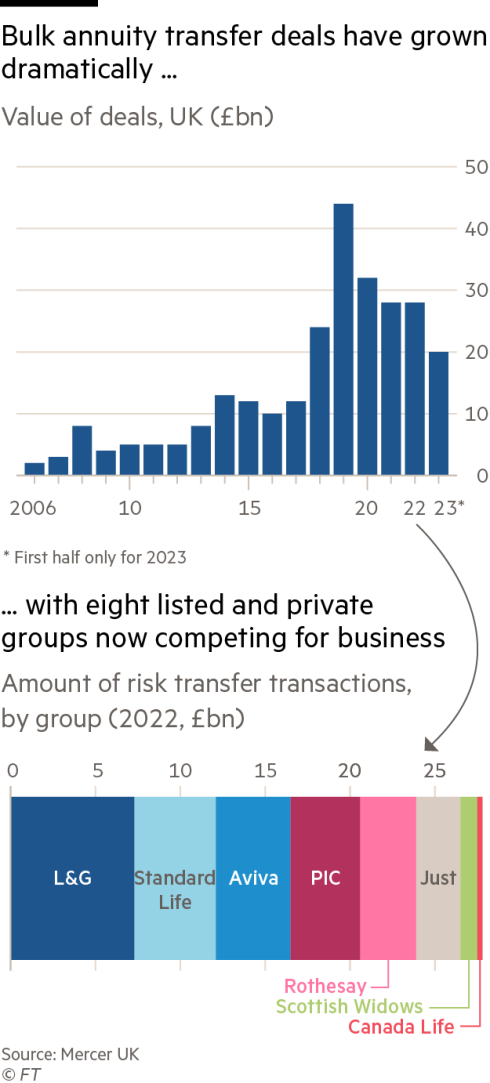

Activity in this once niche area of the financial sector, the so-called bulk annuity market, is at fever pitch as higher interest rates drive up scheme funding levels. That makes a buyout a more realistic option for hundreds of pension funds.

“It’s a huge wave that is breaking now across the bulk annuity market,” says Charlie Finch, partner at consultancy LCP, which advises on deals. LCP estimates that around 1,000 schemes, nearly a fifth of the UK total, are now well funded enough to be offloaded to an insurer. “We really have seen a big step-change over the first half of this year,” he adds. In a note last year, analysts at JPMorgan estimated £600bn of the around £2tn in private sector pension obligations will pass over to insurers in the current decade.

The UK’s biggest transaction was completed earlier this year, when insurer RSA offloaded £6.5bn of its liabilities. That could yet be eclipsed if BP concludes a buyout; the Financial Times reported last week that the oil supermajor was in advanced talks on a deal. With £20bn of business concluded in the first half alone, many in the industry predict 2023 will set a new record for transfers.

Transferring pension liabilities to an insurer means that the sponsoring company no longer has to detail the pension surplus or deficit in its own accounts — or assist with any shortfall — potentially improving its capacity to borrow money, pay dividends, put itself up for sale or pursue a takeover of another company.

Bulk annuity deals are also an increasingly important source of revenue growth for listed insurers such as Phoenix Group, Aviva and Legal & General, who compete with privately owned groups like PIC and Rothesay Life for deals.

“It’s one of the few really growing markets in the UK finance sector,” says James Carter, a bond fund manager at Waverton, which bought into bulk annuity providers’ debt earlier this year.

But the transfer of such large savings pools from a plethora of schemes to just a handful of large insurance companies raises some significant issues. In a speech in April, the Bank of England’s executive director for insurance supervision, Charlotte Gerken, cautioned that the “structural shift” in the provision of retirement income gave insurers “an increasingly important role as long term investors in the UK real economy”.

She called on them to exercise moderation “in the face of considerable temptation” and warned that some bulk annuity providers were expanding their risk appetite “outside their current core expertise”.

Transferring pension liabilities to insurers is also likely to affect investment markets. Closed pension schemes are typically heavy investors in assets that can match the duration of their liabilities, such a gilts, and while insurers take on such assets upon buyout, they tend to want a more diversified asset portfolio to back their new pension contracts.

Some supporters of buyouts say they represent an opportunity not only to reduce risks to companies, but to increase investment in national priorities such as infrastructure and housing.

But there is growing debate over the downsides of turning over pension assets, built up by savers over many years and augmented by tax relief, to insurers who will run them to generate profits for shareholders or their private-equity backers.

“Aside from the security [question], do you want to give those profits to the insurer?” asks Andrew Ward, who leads the risk transfer team at pensions consultancy Mercer.

Buyout basics

Bulk annuity deals are on the rise globally, but the UK is a particular focus of activity because it has high levels of private pension savings. Many of those are concentrated in so-called defined benefit pension schemes, which have around 10mn members. These were originally set up by employers to promise a set level of income to retirees, but improving longevity, changes to accounting rules and consistently falling interest rates have rendered them very expensive to run. Most are now closed, both to new members and further accruals of benefits.

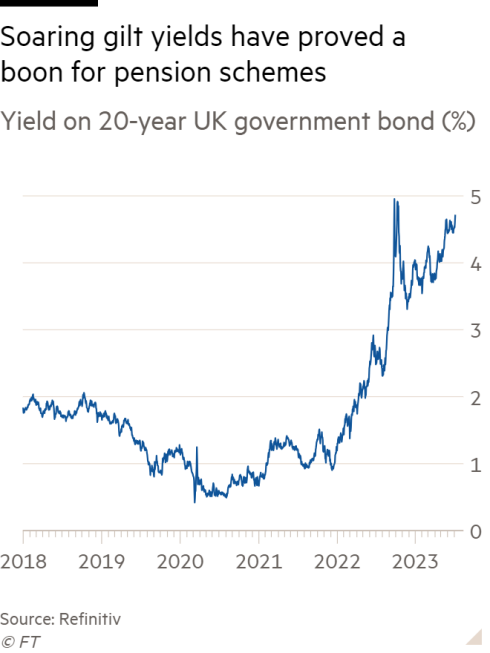

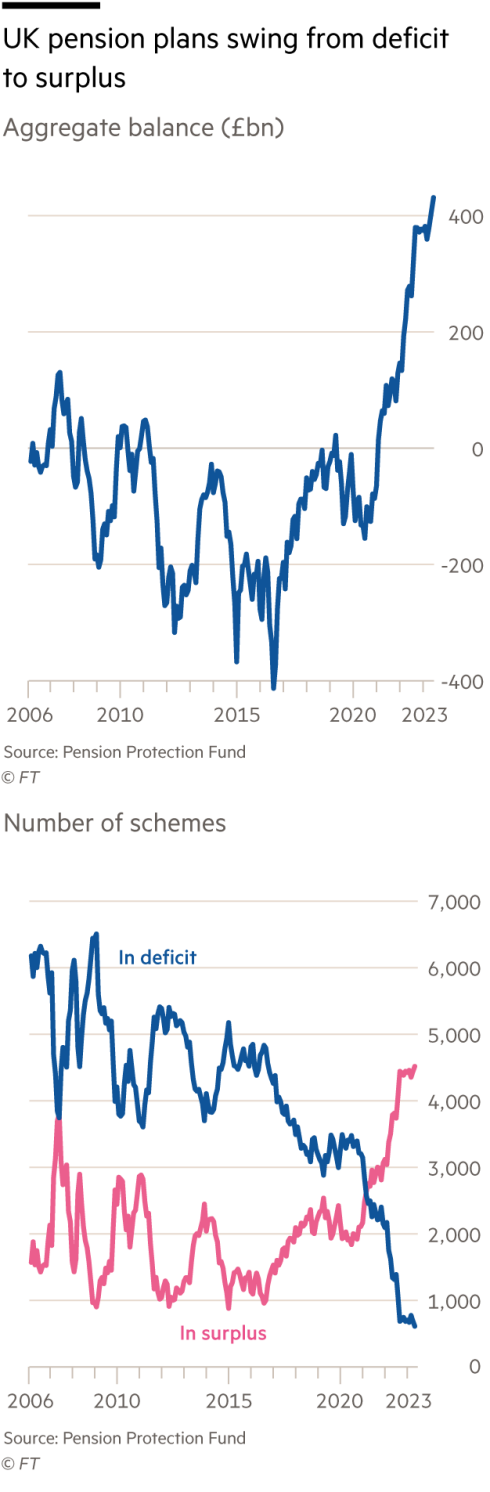

Interest rates on government debt are the basis for calculating the estimated cost of future scheme liabilities in today’s money, and the ultra-low rates that prevailed from around 2009 until last year inflated the net present values of those liabilities and pushed hundreds of schemes into deficit. Sponsoring companies were often called upon to make additional contributions to narrow the gap, diverting cash from more productive uses.

However, recent steep rises in interest rates have led to a dramatic turnround in scheme funding. The 5,000 or so pension plans monitored by the UK’s Pension Protection Fund, which rescues schemes whose corporate sponsor can no longer fund them, swung from a collective deficit of £132bn in 2020 to a surplus of £431bn in May this year. Many are now in a healthy enough position to be transferred to an insurer, a move that safeguards benefits for retirees and relieves companies of the obligation to backstop pension promises.

“Many schemes who were expecting to get to buyout funding [eligibility] in three, five or even 10 years are there now,” says Stephen Purves, head of risk settlement with XPS, the pensions consultancy.

Insurer indigestion

But the ramping-up of buyout activity is testing capacity among insurers. There are just eight bulk annuity providers in the market and they all face constraints on how much capital they can allocate to such transactions and how fast they can hire the staff needed to administer the acquired schemes.

“People is the difficult one at the moment,” says Ward. “Insurers have relatively small deal teams and they have to do a lot of triage.” Purves adds that insurers are now struggling to keep up with demand. “Some are becoming more selective and some require exclusivity to even consider bidding on transactions.”

The PPF told a parliamentary inquiry that capacity in the market was “open to question” and that high administrative and transaction costs could be problematic for smaller schemes — leading insurers to focus resources on bigger deals.

£20bn Value of bulk annuity deals in the first half of 2023. Experts predict this year’s total will exceed the previous peak in 2019Schemes are also facing challenges to get “buyout ready”, including ensuring data held on members’ benefits and their personal details are accurate.

Investment consultants say a bigger issue for some schemes is getting their investments in the right shape. “Insurers are not typically keen to take on illiquid assets,” says Elaine Torry, partner with consultancy Hymans Robertson, leaving schemes needing to dispose of investments such as property, private equity or private debt, which can be difficult to sell in a crisis and may not be eligible for inclusion within the “matching adjustment portfolio” that insurers are required to use to back pension liabilities.

Marcus Mollan, annuity asset origination director at Aviva, says a promised overhaul to Solvency II, the regulatory regime for insurers, should increase the overlap between the assets pension schemes currently hold and what insurers are looking for. But those regulatory changes will not be implemented until the middle of next year at the earliest.

In the meantime, schemes’ exposure to illiquid assets varies from 10 to 30 per cent. Many originally invested in them to help get scheme funding to the point where a buyout is feasible. One insurance executive says pension schemes are telling him it will take “two or three years” to exit such positions and some may need to shoulder a loss on disposal of up to a fifth.

Investment shifts

The shift from company schemes to insurers is also poised to affect the dynamic of the UK’s core financial markets, investors say. Pension funds have been big buyers of gilts and index-linked gilts to back their pension promises, but insurers have different priorities and operate under different rules. They are likely to seek out higher-return investments, such as “build to rent” housing developments, that have been structured to meet solvency requirements.

This dovetails neatly with current political priorities. The UK government wants to unlock some of the tens of billions of pounds in pension savings for long-term investments in areas like social housing and infrastructure.

But market participants predict that pension fund exits will sap what has been a key source of demand for government bonds. “With the central banks stepping back and insurance companies looking elsewhere . . . that marginal buyer of [US] Treasuries and gilts is going away,” says Waverton’s Carter.

Daniela Russell, HSBC’s head of UK rates strategy, says this shift could result in “a new investment landscape with a small group of insurers with a lot of market power”, creating “various risks regulators need to manage”.

She adds that while investment in illiquid assets “is all well and good when market conditions are favourable, they need to be managed prudently as these insurers could potentially act as amplifiers of liquidity risk”.

Gerken warned in her speech that insurers “need to understand, as they take on these vast sums of assets and liabilities, how they may become greater sources or amplifiers of liquidity risk”.

Insurers have privately argued that during last year’s liability-driven investment crisis they remained resilient, while many pension funds had to sell assets or obtain loans to fund margin calls on their derivative positions. But insurance regulators have warned that life insurers could be overly optimistic about their ability to sell down in a crisis.

Insurers’ use of reinsurance is also under the spotlight. When doing deals to take over corporate pension funds they often reinsure, in another jurisdiction such as Bermuda, the risk of retirees living longer than expected.

Some are using so-called funded reinsurance, where they pass on a slice of the liabilities — and the assets backing that slice — to a third-party reinsurer. This frees up capital for them to do more deals but regulators are pushing insurers to consider how they would manage if the reinsurer failed. They say an over-reliance on funded reinsurance could create a “systemic vulnerability” in the sector.

Mick McAteer, a former board member of the FCA and a vocal critic of the Solvency II reforms, has publicly called for regulators to “put a hold on transfers of pension schemes to insurers until we have a full inquiry into financial practices of insurers and their ability to take on pension liabilities”.

Alternatives to buyouts

There is also a growing debate around other ways to secure the future of defined-benefit pension schemes now that the funding positions of many have improved.

One option is to keep the pension obligations — but also the potential rewards from those long-term investments and any changes in assumptions about returns and improvements in life expectancy, which have fallen in recent years.

Another proposal being considered by ministers is to consolidate hundreds of subscale pension plans into larger pools of assets that would benefit from lower running costs and greater diversification. One way to do this would be to expand the remit of the PPF, which currently only takes on corporate pension schemes after their sponsoring employer has failed.

In its recent submission to MPs, the PPF suggested around a third of the UK’s 5,100 defined-benefit schemes could benefit from this approach and that it “stands ready to support and, if needed, deliver any suitable prospective solutions to drive better member outcomes in the future.”

Insurers are nervous such a consolidation effort would divert a significant chunk of business away from the bulk annuity market. “At the very least, it would cause a hiatus in the market,” says one executive at a life insurer, who also warned that it would “slow investment in the economy, in infrastructure” and risk rendering the Solvency II overhaul “pointless”. Insurers’ promises of investment in housing and infrastructure were partly predicated on redeploying assets acquired through bulk annuity deals.

Baroness Ros Altmann, a former pensions minister and a Conservative peer, says it would be “systemically far better to get pension schemes to run on” rather than be bought out, noting that over the decades taxpayers had “spent a fortune” in tax relief to help build up funds. “To hand them to insurers, without ensuring the money has any benefit for the UK economy, seems a real waste.”

But beyond the debates about morality, market function and asset allocation is the powerful impetus from the corporate sector to shed pension liabilities. Many executives are tired of the balance sheet volatility, the ongoing risk and potential demands for top-up payments from scheme trustees. They want out of defined-benefit pension provision and with funding levels improving, see an opportunity to make that escape, market watchers say.

“I’ve never met the finance director of a company in any sector that has a large defined benefit pension scheme attached to their core business that is pleased to have it,” says Phoenix chief executive Andy Briggs.

“As soon as they can afford to buyout, most would move to [do so].”

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Ian Smith