Quick blood tests to spot cancer: will they help or harm patients? But some scientists question if they really work

Valerie Caro is perhaps unusual in that she considers herself fortunate to have been diagnosed with cancer.

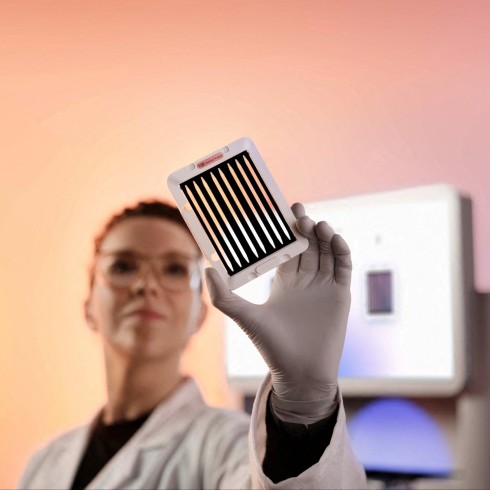

The real estate broker from Flagstaff, Arizona, spent $950 last year on an experimental blood test called Galleri which detected gallbladder cancer at an early stage. Following scans to verify the diagnosis, Caro had surgery to remove a tumour and underwent chemotherapy. She is now in recovery.

Grail published the results of a study of almost 6,700 participants aged 50 years or over in September last year. Of 92 participants flagged with a potential cancer signal, about 35 participants were diagnosed with cancer. All but 10 of these diagnoses were for cancers that did not have routine cancer screening programmes in place. Fifty-seven were false positives, almost a third of which prompted an invasive procedure to rule out a cancer diagnosis.

Promising results from early MCED test trials led to a rush of start-ups and investment. In 2020, Illumina bought Grail back for $8bn, citing its ability to “help transform cancer care”. The transaction attracted the attention of European and US antitrust authorities, which said the tests had the potential to “revolutionise” the fight against cancer. Last year the EU ordered Illumina to unwind the transaction, arguing it would dent competition in the MCED market since Illumina would have an incentive to cut off Grail’s rivals from using its sequencing technology.

Grail will soon face competition in the US from Datar Cancer Genetics, which inked a $250mn deal last year with US-based diagnostic laboratory company Artemis DNA to fund the rollout of its own MCED test called TruCheck in the US and Vietnam.

Other competitors such as Exact Sciences, based in Wisconsin, and San Francisco’s Frenome, a start-up backed by Roche, are racing to launch their own tests.

“When interest rates were low and cash was easier to come by there was huge excitement about the potential for these tests and companies were able to raise billions of dollars of investment,” says Vijay Kumar, an analyst at Evercore ISI, an investment bank.

But their success rests on getting regulatory approval. In the US, because Galleri has not yet won approval from the FDA, it is not covered by US government health insurance schemes. “This [approval] remains an open question that will depend on the results in ongoing trials,” Kumar adds.

Illumina and Grail increased their US lobbying spending fivefold to $14.6mn in 2021 and 2022 when compared to the previous two years. Illumina also expanded lobbying in Europe and the UK, where it hired former prime minister David Cameron as an adviser in 2019 shortly before winning a gene sequencing contract with a company owned by the Department of Health and Social Care. (Illumina says it no longer employs Cameron as a paid adviser.) In November 2020, the NHS struck its deal with Grail to pilot Galleri — a collaboration that is key to winning regulatory approval. Interim results are expected next year.

An uncertain diagnosis

The full-throttle corporate race to persuade governments to integrate MCED tests in national screening programmes is raising concerns among some cancer specialists.

Research shows there are drawbacks to screening for certain types of cancer, particularly for those where there is limited evidence that early detection and treatment saves lives. Tests can sometimes produce a cancer signal, even when the body is cancer-free. Such false-positive results can lead to more tests or treatment, which can carry potential risks and cause needless anxiety.

Screening can fail to detect cancers, which provides a false sense of security and may cause some patients to neglect symptoms. About 20-30 per cent of women with breast cancer have tumours that are missed by mammogram screening, according to research.

Screening can also pick up slow-growing tumours that don’t cause symptoms during a person’s lifespan, a process known as over-diagnosis. “Over-diagnosed patients . . . can’t be helped because there’s nothing to fix, but they can be hurt in the process,” said H Gilbert Welch, a cancer epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

In 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommended against screening all men for prostate cancer using a prostate-specific antigen blood test, concluding the benefits did not outweigh the risks. The advice reflected concerns about side effects linked to follow-up testing via unnecessary biopsies and treatment, which include erectile dysfunction and incontinence.

Welch says the new generation of MCEDs are a remarkable technology. But it is a mistake to rush their rollout without the necessary long-term studies that prove they save lives. “My guess is this is a quagmire that costs a lot of money to governments and individuals. If you test all Americans aged 50 and above it costs $100bn a year,” he says.

“Such a policy would lead people to go through a lot more testing. It will make some people poor and make others excessively worried and I don’t think it’s really going to change mortality much, if at all,” he adds.

Some doctors already prescribing the Galleri tests to patients say they have reservations. Dr Vershalee Shukla, who runs a cancer screening programme in Scottsdale, Arizona, for firefighters — a high-risk group due to their regular exposure to environmental toxins — says the Galleri test missed the cancer in almost 50 individuals out of roughly 3,000 tests she conducted over two years. The test accurately detected three cancers and produced two false positives, she adds.

Firefighters in the nearby city of Mesa are offered additional screening options under a publicly funded programme, including a full-body MRI scan. One of the patients, Drew Mogalian, says that after getting a clear result from Galleri he only went for a follow-up MRI scan after a discussion with his wife about the death of a colleague from cancer.

“The full-body MRI came back and showed a brain tumour,” he says.

Mogalian had a biopsy in September which confirmed the diagnosis. He has recently completed a course of chemotherapy and is awaiting further results.

Dr Shukla says her experience testing the firefighters provoked mixed emotions. “As an oncologist, I love the concept. Cancer is a pandemic and we need a safe way to screen younger patients and blood tests are very safe. There is no radiation and it’s minimally invasive,” she says. “But it missed almost 50 cancers. This provides a false sense of security to patients, who may not want to do additional screening that could pick up their cancers.”

She says it is “upsetting” that Grail is still promoting its test to firefighters even when she presented the company with her evidence. Additional testing is needed in younger, high-risk populations if the test is going to be marketed to them, she adds.

Grail says that all cancer screening tests have both false positives and false negatives, many of which are at a higher rate than Galleri. One in eight mammograms produces a false negative result while the rate of colonoscopies can be between 7 per cent and 25 per cent, according to Grail. Screening tests run on small populations will see different results based on age and risk, says the company’s chief medical officer, Jeffrey Venstrom. “At the national level, our cancer signal detection rates are consistent with our clinical studies and epidemiological modelling,” he says, adding that Galleri is finding asymptomatic, potentially deadly cancers that would otherwise have gone undetected.

Ofman, Grail’s president, says that with the NHS trial the company is undertaking the largest randomised control trial ever for a MCED test. The trial would “once again validate the performance” of Galleri and measure how it can reduce the number of cancers detected in their late stages, he says, adding that he feels a sense of “urgency” and “responsibility” to get tests out to as many patients as possible, as quickly as possible.

But the NHS trial will not measure whether Galleri reduces mortality rates when used as a screening test — that would take a decade to produce definitive results.

Pharoah of non-profit Cedars-Sinai says the trial is “seriously flawed” because the first and foremost thing you should measure is whether a test that would be applied to a screening programme reduces mortality. “Just because you reduce late-stage disease does not mean you will reduce mortality from cancer or other causes,” he says.

Susan Bewley, a consultant obstetrician and emeritus professor of obstetric and women’s health at King’s College London, says the problem with MCED screening is that the more of this you do on healthy people the more errors you get.

“This sort of screening test could bankrupt the NHS, prioritise people who are well over those who are sick, and make people ill. This is ethically dubious,” says Bewley. “Before these tests are rolled out we need to follow hundreds of thousands of people over many years to determine if the treatments actually stop them from dying.”

Bewley is concerned that the way the NHS trial is structured means that Grail is likely to claim success even though many of the people with early-stage cancer may never have become ill.

“Screening is like a modern form of bloodletting with leeches: if you died it’s because we didn’t leech you early enough and if you didn’t die then the leeches saved you,” she says.

Graphic illustration by Ian Bott

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Jamie Smyth