Amanda Feilding – the first lady of LSD Today, her psychedelic reality is starting to make sense

A low mist is hovering above the fens on either side of the mile-long track to Beckley Park. This patchwork of marshland is said to have inspired Lewis Carroll’s mind-bending chessboard in Alice Through the Looking Glass, and on this eerie morning such strangeness tilts the perspective. The feeling is heightened by the knowledge that at the end of the path is a house not only steeped in intrigue dating back to King Alfred, but one whose current châtelaine, Amanda Feilding, has for almost 60 years been a passionate agitator in “The Psychedelic Renaissance”.

The track winds to a wide-fronted and narrow-waisted Tudor house built in dark-red diaper brick. Cosseting it are three greeny-black moats, whose patterns play games with logic. One streak of water comes from nowhere to run along the face of the house, while another snakes behind then disappears, engulfed by a new vision: a maze of towering topiary that points and undulates, hides and exposes. To the south of the main building is a moss-covered caravan engraved with hearts and birds; beside it, a converted cowshed with an arched and iron-studded wooden door. Here, sheltering from the wind, is the beating heart of the Beckley Foundation.

Feilding created this non-profit organisation in an outbuilding of her family home in 1998 following a frustrating 30-year one-woman crusade. Her vision: to work with leading scientists from around the world to establish the true effects of psychedelics. The foundation’s aim is to reform global drug policy based on scientific evidence and safely reintegrate psychedelics into society. In 2016, its Beckley/Imperial College London study was the first of its kind to demonstrate that psychotherapy in conjunction with psilocybin (the psychoactive ingredient in magic mushrooms) could be effective for treatment-resistant depression.

Feilding was born at Beckley in 1943, the fourth child to parents she describes as “absolutely charming” but also “anarchist in intellectual temperament”. She remembers her farmer/artist father saying, “Whatever the authorities or the government tells you to do – do the opposite.” It was the middle of the war, and the “freezing” house was packed with family escaping from London, as well as refugees. “We ran wild,” she says. Upstairs, a bedroom now drenched in golden tones and centred around a four-poster bed upcycled by Feilding was the nursery. A glass-fronted cupboard in the corner is filled with the dead-eyed plastic dolls she once played with.

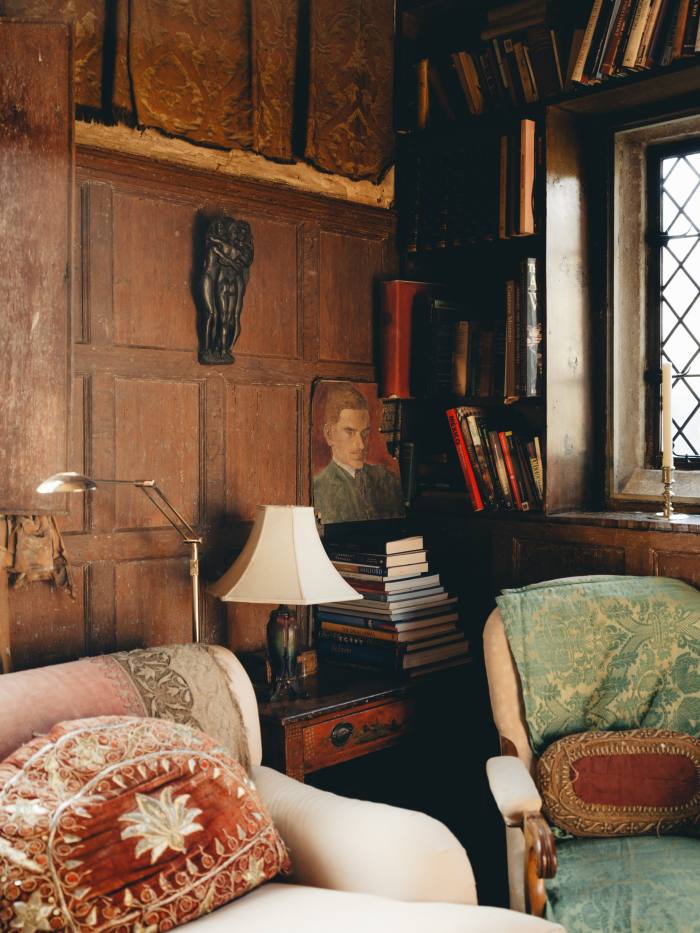

The house is a jigsaw of rooms that interlock rather than running off a central space. It’s rich in historical grandeur but also, with its modestly sized rooms dominated by huge stone fireplaces, exudes cosiness. Feilding’s grandparents bought the house in 1919, custodians in the footsteps not only of King Alfred, but also Henry III (who gave the then-incarnation of the house to his brother, the scheming Earl of Cornwall); Edward II (who gave it to his rumoured lover, Piers Gaveston); the Black Prince (father of Richard II); and Lord Williams of Thame, who built the current house on the medieval site. “The mists come in and it’s a magical place,” says Feilding. “Somehow there’s a strange magic, maybe partly because of the history that bubbled here.

“It’s a good setting for ideas,” she continues. “It’s got a feeling of being an island outside culture in which you are free to explore.” Her grandmother, she tells me, welcomed a merry-go-round of creatives including Aldous Huxley, who set his novel Crome Yellow at Beckley after visiting for tea in 1921. Presciently, his book The Doors of Perception explores the effects of mescaline on consciousness.

“As part of my work, I entertain people two or three times a week,” says Feilding over lunch in the slim puzzle piece of a dining room, its wooden table and tapestry-covered chairs running alongside a vast fireplace and 18th-century lighthouse reflector. “Lots of seminal meetings have happened here.” Most recently there have been American philanthropists; Feilding is keen for them to support the US-based non-profit arm.

She tells me that the latest fundraising push is to support her new “double-headed” research programme, created in collaboration with scientists from King’s College London, Cornell and the University of Basel, to name but three. This “deep exploration of LSD” will look into, on the one hand, the mystical and spiritual effects of full dosage, and on the other, therapeutic applications for microdosing in ageing communities – including those with Alzheimer’s – and a new concept for care homes. “This project is the culmination of what I’ve been wanting to do,” she says.

“My hope is that the concept of altered states of consciousness is accepted by society and that it can be beneficial for those who want it,” she says of her holy grail. Her hypothesis is that psychedelics “increase the energy to the brain, which must logically be a good thing. It increases neuroplasticity. It increases neurogenesis – and that is the basis of learning and adapting. And that’s what humanity must have to survive… There’s a growing epidemic of mental illness – we’re a very troubled animal – and we need to adapt to a very different world. And consciousness is key. What is more key, in a sense?”

Psychedelics are not the extent of Feilding’s experiments with consciousness. In the bigger of two living rooms – hung with glorious yellow curtains, and grand images of Susanna and the Elders and The Death of Seneca – a skull peeks out from behind some flowers. Six large coin-sized holes are bored into it. A gift from her second husband, James Charteris (the 13th Earl of Wemyss and 9th Earl of March, and the reason Feilding is a countess), it dates from “thousands of years ago” and is a symbol of their shared fascination with trepanation.

Dating from the Stone Age, the practice of drilling a hole in the skull is believed by advocates to increase blood flow to the brain, increasing energy, creativity and higher states of consciousness. Aged 27, Feilding practised the act on herself with a dentist’s drill, while partner Joe Mellen filmed it as a documentary “artwork” called Heartbeat in the Brain. “All you’re doing is removing a piece of bone so that the membranes surrounding the brain can expand as much as they want to. So you are giving back full systolic pressure to the muscle and the benefit of that is a little bit more blood in the cranial cavity in the capillaries... and the benefit of that is increased energy.” Supposedly, straight after, she wrapped her head in a bandage and a turban and headed out to a party. So impressed was she with the effects that she not only convinced Charteris to be trepanned several decades later, but also twice stood for Parliament, in 1979 and 1983, campaigning for “trepanation for the National Health”.

Feilding describes standing for Parliament as a “conceptual artwork”, a term she also levels at the Beckley Foundation. “I think it’s a work of art, and I think it’s a rather successful work of art,” she says. “My aim was to no longer be Amanda Feilding, a female with no letters to my name, [and to] become a foundation and get the best scientists in the world, put them on my board. That’s why it’s a conceptual artwork.” Board members have included the late neurobiologist Sir Colin Blakemore, and collaborators the former government adviser Professor Nutt. She is proud of her creation: “I did it to change the world. Which it has helped to do.”

This year, the foundation marks its 25th anniversary and Feilding has turned 80. Birthday toasts included those from biologist and author Merlin Sheldrake, who called her “a passionate and fearless advocate for psychedelic research [whose] efforts have helped transform the study of these remarkable compounds”, and Dr David Luke, associate professor of psychology at the University of Greenwich, who said: “I can think of no one in the UK who has worked harder and more consistently than her, over six decades, to bring psychedelics back into the light of consciousness in both science and drug policy.” Coincidentally – or perhaps not at all – 80 years of LSD is also being celebrated. Although Swiss chemist Albert Hofman synthesised the compound derived from the ergot fungus in 1938, he only appreciated its properties five years later when he ingested 250mcg and had an interesting cycle ride home – hence the name given to 19 April by the psychedelic community: Bicycle Day.

Feilding feels her role in “The Psychedelic Renaissance” has been pivotal: “In a sense I did take on the world’s law,” she says. “And I think we’ll win. I’ve always felt it was the winning side.” Over the decades, she has been called everything from “the crackpot countess” and a “hedonistic hippie” to “the Queen of Consciousness”. Now, more than $3bn has been raised by psychedelics prospectors, many of them from Silicon Valley, to explore their benefits in conditions from depression and anorexia to PTSD.

She is “delighted” also that her two sons (with Mellen) have “picked up the baton”. Each has taken Beckley in a new, for profit, direction: Rock Feilding-Mellen, 44, is developing Beckley Retreats, whose first “psychedelic healing retreats” launched this year in Jamaica and the Netherlands, and whose round of seed funding in October 2022 saw a $1.5mn investment. Younger son Cosmo is the CEO of Beckley Psytech, a biotechnology company exploring the potential of synthetic psychedelics to be licensed for neuropsychiatric treatments; it announced in February that it had received Investigational New Drug (IND) approval from the FDA for a global study.

Feilding, however, maintains a certain distance: “I’m not against profit. But my aim is to do good for the world. And I don’t want that contaminated by, you know, profit.” She plans to continue focusing on the foundation’s specific quest from her HQ at Beckley Park. “It is part of my soul. I couldn’t imagine living without Beckley. I have always loved it as a being. I think it is rather primal.”

Beatrice Hodgkin will chair a session on psychedelics at the FTWeekend Festival at the Kennedy Center, Washington DC, on 20 May. For in-person and online tickets, visit ftweekendfestival.com

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Beatrice Hodgkin