China’s fake science industry: how ‘paper mills’ threaten progress

As part of his job as fraud detector at a biomedical publisher, John Chesebro trawls through research papers, scrutinising near identical images of cells. For him, the tricks used by “paper mills” — the outfits paid to fabricate scientific studies — have become wearily familiar.

They range from clear duplication — the same images of cell cultures on microscope slides copied across numerous, unrelated studies — to more subtle tinkering. Sometimes an image is rotated “to try to trick you to think it’s different”, Chesebro says. “At times you can detect where parts of an image were digitally manipulated to add or remove cells or other features to make the data look like the results you are expecting in the hypothesis.” He estimates he rejects 5 to 10 per cent of papers because of fraudulent data or ethical issues.

The soaring output has sparked concern in western capitals. Chinese advances in high-profile fields such as quantum technology, genomics and space science, as well as Beijing’s surprise hypersonic missile test two years ago, have amplified the view that China is marching towards its goal of achieving global hegemony in science and technology.

The problem is that no publisher — even the most vigilant — has the capacity to weed out all the frauds. Retractions are rare and can take years. In the meantime scientists may be building on a fake paper’s findings. In the biomedical sphere this is all the more worrying when the aim of a lot of research is the development of treatments for serious diseases.

‘Sea turtle’ backlash

The scrutiny of fake Chinese research has exacerbated the mistrust between western and Chinese academic institutions, which was already growing as a consequence of fraying geopolitical relations — and allegations that researchers from China are using their time in overseas labs to steal intellectual property.

“In view of the increasing geopolitical tensions, we are conducting background checks [of applicants from China] in relation to our grants and other activities, whenever and wherever this is relevant,” says Mads Krogsgaard Thomsen, chief executive of the Novo Nordisk Foundation, one of Denmark’s largest funders of academic research. “We do this based on recommendations from the authorities and in collaboration with our grant recipients.”

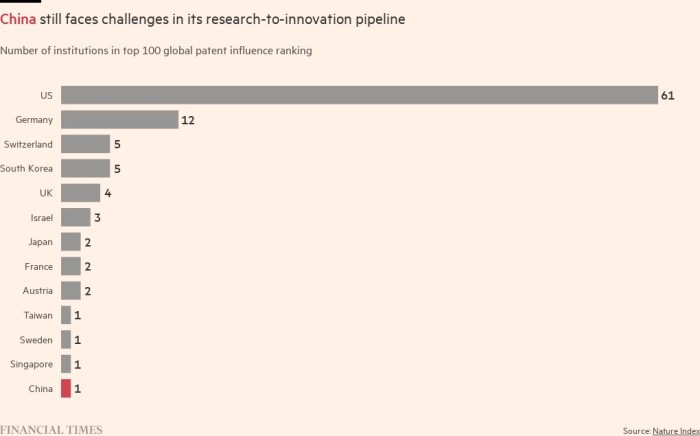

China has swiftly and indisputably become the world leader in the commercialisation of research as measured by patents. The World Intellectual Property Organization says the country’s patent office received 1.6mn applications in 2021, compared to 600,000 for its US counterpart.

Such activity has unsettled western governments, who have erected barriers for many Chinese science and tech researchers coming to their universities, fearing that these academic exchanges have contributed to the country’s rapid global ascension. Several Chinese researchers in the US have been arrested under suspicion of leaking intellectual property to China under a Donald Trump-era programme to root out economic espionage.

“Some of the growing hostility and suspicion [in the west] is around legitimate areas of concern, some of it is paranoid and daft,” says James Wilsdon, professor of research policy at University College London. “But there are now many examples of Chinese science and technology espionage and dodgy practices.”

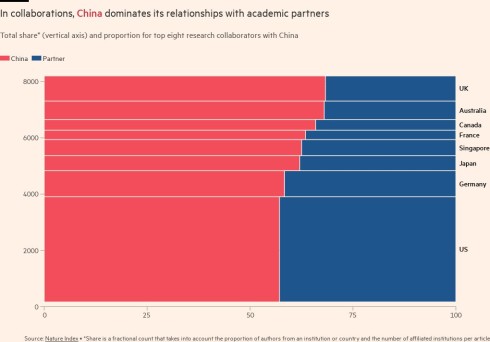

As countries that have been “big contributors to the growth of collaborative science” decelerate their engagement, the prospects for China’s research output “are far more uncertain” than they have been in the recent past, Wilsdon adds.

In China, academics with international training are most likely to be published in leading publications. Qingnan Xie, an intellectual property expert at Harvard University, found that 76 per cent of articles published in the Nature and Science journals from Chinese addresses had an author who had studied overseas before returning to the mainland.

Beijing has bankrolled the massive outbound movement of science graduates to study in universities from Tokyo to San Francisco and London through scholarships and grants, providing incentives to return to the mainland once they’ve completed their education.

This so-called “sea turtle” strategy is one pillar in a broader policy to develop an indigenous scientific and technological power base. It has “fostered international collaboration and lifted standards in China”, says Steven Inchcoombe, president for research at Springer Nature.

As geopolitical tensions erode the trust needed to keep collaborative ventures alive, scientists say both sides are set to lose out. For many labs worldwide, Chinese researchers are a crucial source of labour to participate in large-scale experiments. Western researchers benefit from access to cheap and well-educated Chinese PhD students who can help bolster their findings by running experiments.

“China is very good at application and refinement,” says Inchcoombe. “But the culture is more one of systematic thinking building on other research, whereas the west tends to applaud individualism. China doesn’t seem to see the need for standout heroes in the same way.”

The physics lecturer in Beijing makes a similar point. “American or British scientists tend to have breakthrough ideas and do truly innovative research,” he says. “Chinese are quick learners. They help to find evidence and make the framework more solid.”

Carsten Fink, chief economist at the World Intellectual Property Organization, says Chinese innovation is strikingly successful when researchers are able to “leapfrog” over existing technology into a new field. One example is Beijing’s strategy of focusing investment on electric vehicle production rather than the already saturated combustion engine market. Another is the country’s domination of global solar panel production.

Jonathan Adams, chief scientist at ISI, points out that China’s international collaborations are “strongly biased towards physical sciences: information and communication sciences, materials and areas like that — and particularly so in the US. In some areas of US research, 80 per cent of publications have a China address for a co-author.”

Discovering the extent of Chinese involvement in US research had come as “a complete surprise” to some American policymakers, Adams says. “They were quite unaware of how far Chinese research had moved to underpin what they were doing. The most highly cited US-authored research in a lot of these technology areas is co-authored with China.”

Advocates for science in the US are working to ensure that collaboration with China does not collapse completely. “Our culture of science is a beacon for Chinese scientists,” says Sudip Parikh, chief executive of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “They help to enrich our economy and our labs. These intellectual relationships matter and it is important that we don’t lose the big picture of the benefits of international collaboration.”

If scientific ties with the west break down, the individuals who will suffer most are diligent Chinese academics, as an atmosphere of distrust and the country’s reputation for fraudulent research make it more difficult for them to gain international recognition.

“The worst impact is on sincere Chinese researchers,” says Bimler. “There is enough junk coming from China that researchers privately admit that they don’t read papers if they’re from a Chinese source . . . Scientists don’t have time to determine what is junk and what isn’t.”

Additional reporting by Xueqiao Wang in Shanghai

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Eleanor Olcott