UK struggles to get its long-term sick people back into work

Claire Shepherdson spent seven years on employment and support allowance, a UK sickness benefit, after her autism, dyslexia and learning difficulties left her struggling to find work.

Now, supported by carers, the 37-year-old is happily settled in her own flat, has had her art exhibited in a local gallery and is loving her work as a cleaner at Bury Grammar School near Greater Manchester, saying she feels “really honoured” to have the job.

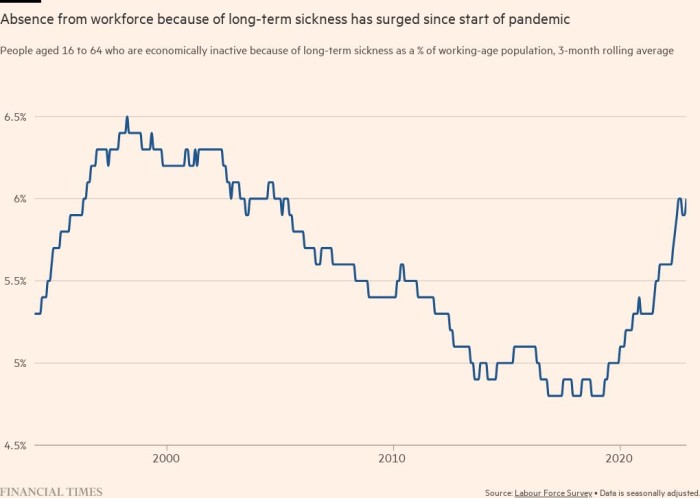

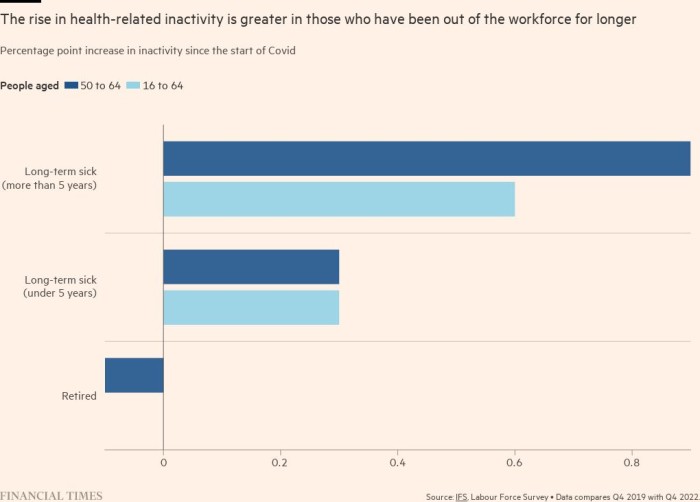

While attention has focused on the large number of over-50s who opted to leave work during the pandemic, ill-health is the largest contributor to this inactivity for the first time since records began. It accounts for 29 per cent of the total, compared to 25 per cent before the Covid pandemic.

Nor is it only the middle aged or elderly who are too sick to work. The LFS shows that the largest percentage increases since the start of the pandemic have been among younger people. Rates of inactivity due to long-term sickness rose 26 per cent for 16 to 24-year-olds in the three years from September 2019 to September 2022.

While the UK is not the only country seeing a rise in the numbers on sickness benefit, it is out of step with the majority of the OECD economies. All OECD members experienced increased rates of inactivity in the first half of 2020 but the UK is among the fifth that still have higher rates than before the pandemic, according to the Office for National Statistics.

But it is too easy to suggest that the UK population is simply sicker than international counterparts, suggested Torsten Bell, chief executive of the Resolution Foundation, which studies low-to-middle earners. He pointed out that many other countries have also seen a marked rise in the number of people suffering mental ill health, as well as some increase in physical ill health due to ageing populations.

One reason that a bigger proportion of the UK population is on disability benefits may be that claimants are better off than they would be on unemployment payments. Of the 34 OECD countries that submitted data, the UK has the least generous provision after two months as a proportion of previous in-work income. Even after a year, only four countries perform worse.

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Amy Borrett