Has DNA sequencing expert Illumina taken the wrong path in search of holy grail?

In September, the world’s biggest genome sequencing company hosted Barack Obama, Bill Gates and other luminaries at its annual forum in San Diego, predicting its latest generation of machines would help “change the world”.

Illumina could make the case that it had already done so with its existing technology. It provided the machines that in 2020 decoded the genetic sequence of the virus that causes Covid-19, enabling researchers to develop vaccines and drugs in record time.

Surging demand for its technology and a pandemic-era biotech investment boom caused the market capitalisation of the company — which has an 80 per cent share of the sequencing market — to peak at about $75bn in August 2021.

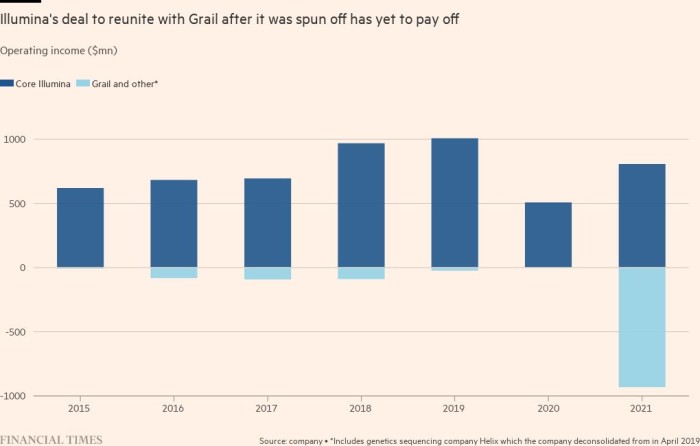

Analysts say the bad news is prompting investors to question the company’s strategy of buying Grail, which Illumina forecasts will generate an operating loss of $670mn in 2023 on revenues of $90-110mn. Illumina shares are hovering near five-year lows and it is now worth $33bn.

Dan Brennan, analyst at Cowen, an investment bank, said many investors are not “fans of the deal” and it came up in almost every conversation he had with them.

He said Illumina has over the past decade been an attractive, high-growth investment because it sells its sequencers at high prices (up to $1.25mn each) and has recurring revenues from the reagents and other products required to operate them. Grail is a riskier business because it is burning lots of cash and there is uncertainty about whether its technology will be a commercial success, said Brennan.

Twelve years ago, the process cost around $10,000. Illumina’s benchmark in 2020 was around $600 but it plans to reduce this to $200 with its new machine.

Another early-stage company Ultima Genomics has said it can cut sequencing costs to $100. MGI, which was spun out from BGI last year through an IPO, has begun selling its sequencers in the US market following the expiration of key Illumina patents last year.

“Illumina has really been dominating the market for more than a decade and customers need competition,” said Molly He, a former Illumina executive who is chief executive and founder of Element Biosciences.

She said Illumina started offering Element customers big discounts when the company entered the market last year. But Element has also benefited from increased interest in its products from Grail competitors that use DNA sequencing, she added.

“They [customers] are obviously worried about what is going to happen after Illumina acquires Grail: would they still have access to high quality, low cost sequencing?”

Illumina said discounting was a standard business practice and rejected any suggestion that its ownership of Grail would influence its relationship with customers of its DNA sequencing business. But this was a key concern highlighted by European authorities when they blocked the Illumina/Grail merger.

Vijay Kumar, analyst at Evercore ISI, an investment bank, said it was a “big, bold and aggressive” move by Illumina to acquire Grail because Illumina was paying $8bn for a company with very little revenues at the time. But the decision to close the Grail acquisition despite opposition from Brussels was a gamble, he said.

“Francis bet big on this,” Kumar said. “Ultimately the buck has to stop with the CEO.”

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Javier Espinoza