Drug makers and governments at loggerheads on prices

If there was some sort of a truce on drug prices between big pharma and politicians during the coronavirus pandemic, it ended last week in spectacular fashion.

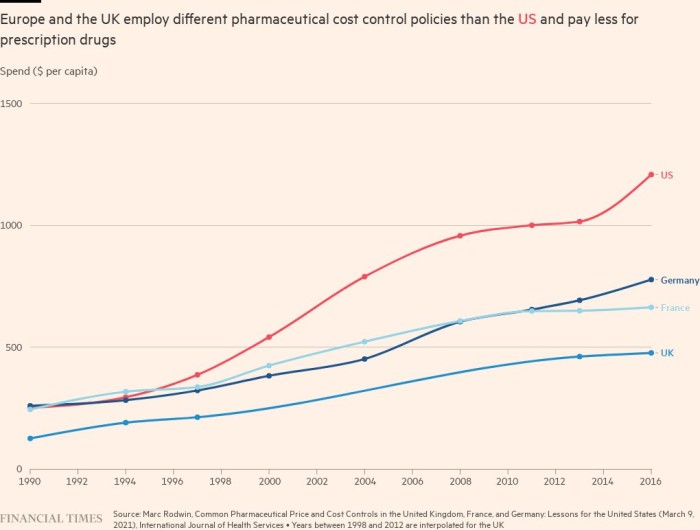

US groups Eli Lilly and AbbVie pulled out of the strictest price regime in Europe — after NHS spending on branded drugs in 2022 handed the industry £3.3bn in clawback costs, about 26.5 per cent of UK sales.

Drugmakers are also considering whether to withdraw from an agreement with the French government, according to one person familiar with the discussions.

Under the UK’s most recent pricing deal, which was agreed in 2019 and is set to expire this year, if the NHS bill for drugs grows more than 2 per cent a year, the pharmaceutical industry pays the difference. Other countries with similar deals tend to share the extra costs.

The pandemic increased demand for drugs to treat patients with Covid-19 and other conditions. But it is not the sole reason for rising costs: high prices for new medicines for cancer and rare diseases are also a factor. The NHS has agreed, for example, to prescribe certain expensive but transformative treatments such as Novartis’ Zolgensma, which treats spinal muscular atrophy, and Orkambi, a drug made by US biotech Vertex for cystic fibrosis.

Under pressure in some of their biggest markets, pharmaceutical companies say they will have no choice but to cut investment — and the well paid jobs and growth that politicians like — if they cannot reach better pricing deals.

Eli Lilly said that Europe’s focus on spending cuts is “detrimental” to its ability to attract research and development, clinical trial and manufacturing investments. While Bayer, which is headquartered in Germany, told the Financial Times it will shift the focus of its pharmaceutical business to the US, accusing Europe of being “very innovation unfriendly”.

But Marc Rodwin, a law professor at Suffolk University in Boston, who has written a number of papers on pharmaceutical pricing systems, said people in the UK health department do not see this as a “serious concern”, partly because it can make financial sense for companies to do their research in the UK and the US.

Cueni at the IFPMA said the industry’s warnings should not be dismissed as “pure rhetoric”. He said while R&D investment decisions are driven by a country’s science base, pricing policy does affect overall investment. A recent report for the European industry group showed a widening gap in R&D investment between the US and Europe in the past 20 years, while China has become an important alternative base for research.

“You do have a choice. Not only are there great scientists in the US, nobody beats them there, but you also get a return on investment in a tough environment,” Cueni said.

The industry is also worried that R&D productivity is falling. Deloitte found that the average cost of drug development had increased to $2.3bn by 2021, while the average annual peak sales per drug had fallen to $500mn, continuing a trend of decline in the past decade that was only briefly interrupted at the height of the pandemic.

But total pharmaceutical sales are forecast to grow at an annual rate of 6 per cent between 2022 and 2028, according to data research firm Evaluate Vantage, and the world’s largest pharma companies currently have $1.4tn of firepower to do deals, including cash and debt, according to EY.

Rodwin said the bigger threat would be if pharma companies stopped selling certain drugs in Europe.

So far, drugs have mainly been withdrawn after European health authorities raised questions about whether they were good value. Last year, Boston-based Bluebird Bio pulled Zynteglo, its one-off gene therapy for the blood disorder beta thalassaemia, from the European market after failing to persuade the German government to cover its $1.8mn price tag. The company recently launched the same drug in the US for $2.8mn.

Andrew Obenshain, Bluebird chief executive, said European payers were still thinking about prices as if all patients required repeat prescriptions for chronic disease.

“It ended up being in a negotiation that really reflected just historical drug price negotiations and not a reflection of the value of the therapies. So that was very disappointing,” he told the Financial Times.

When European health authorities head to the negotiating table, they will have to come to terms with a drug industry that is no longer focused on producing daily pills to pop.

Whereas drugmakers used to make a little from each patient in a large market, increasingly they are focused on charging more to treat small subsets of patients, with rare diseases, or in oncology, with a certain mutation in their tumour.

Governments have not been giving their health systems more money to cope with this change.

Alistair McGuire, head of the health policy department at the London School of Economics, said European countries toughened their policies because of these higher prices. “The rates of growth in prices, especially for oncology drugs, have been quite remarkable. Steep in a very short period of time,” he said.

The UK health department said it had delivered a record number of access agreements under the last voluntary deal, and is open to ideas about how the next scheme should operate. The industry has floated new models, such as paying only if a treatment works, or a flat fee for as much of a drug as is required.

Torbett from the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry admitted it is hard for anyone to plan for innovation. “The trouble with the public sector or anyone budgeting, is all of a sudden we can do something for patients that we couldn’t do before. But we have to find the money for it.”

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Leila Abboud