Bootcamp, but make it Positano

“The thing is, the power of the dolce vita brand is now so entrenched that people only associate this area of Italy with a few things,” says Francesco Sersale as he marches up a mountain path on which the autumn flora is offering a final flourish. Those things are, he says, as follows: eating lots of pasta, posing for selfies at sunset against the commune’s dusky walls, and sitting on the beach. “People come and they watch the sea and hold hands and take a boat trip. And it’s all very romantic and lovely, and then they leave,” continues Francesco. “Not that there’s anything wrong with that, of course. But very few people realise that there’s an entirely different side of Positano if you just look in the other direction.”

Francesco is the third generation of the Sersale family to be involved in Positano’s Le Sirenuse, a sprawling oxblood-coloured testimony to old-world glamour that first opened in 1951. The hotel has done much in the intervening decades to cultivate the very sensibility Francesco is unpicking: thousands of tourists – mostly American, mostly couples – flock to the hotel’s terraces each summer in search of their own slice of lemon-scented Amalfiana, and the Sirenuse sits at the fore of any itinerary for affluent adventurers in search of their own neo-realist Italian fantasy. Blame John Steinbeck, that midcentury Baedeker who arrived in Positano on an assignment for Harper’s Bazaar in 1953 and was quickly captivated by the “old family house converted into a first-class hotel” managed by the Marchese Paolo Sersale, who happened to be mayor of the town.

“Positano bites deep,” wrote Steinbeck in his dispatch. It’s an observation that has become an unofficial slogan for Le Sirenuse, which sells T-shirts printed with those very words from its boutique opposite the hotel.

Steinbeck was smart enough to recognise the geological and economic challenges presented by promoting a town that clings so precipitously to a vertical escarpment. “There are about 2,000 inhabitants in Positano and there is room for about 500 visitors, no more. The cliffs are all taken.” He clearly didn’t reckon on social media. In fact, some five million visitors now chug along the Amalfi Coast each summer, and its towns have become an essential feature of the influencer life – #AmalfiCoast has more than 514m views on TikTok. Having witnessed the tidal surge of visitors attempting to move along Positano’s narrow lanes on the last Sunday in October, I can only imagine the glorious absence of visitors that Steinbeck once enjoyed.

For Francesco, who joined the business in 2020 after a stint in New York, the future of Positano lies in the opportunity to open up the region to travellers by offering a quiet extension to the season. For the past year, he has been working on Dolce Vitality, a week-long programme, open to 24 guests, of walking, sunrise yoga, massage and fasting (or let’s call it very mindful eating) that bookends the summer months – when the weather is cooler, the plant life is more abundant and the crowds are largely gone.

So far, so brutal. And I’m doing an abridged version of the official week-long programme, which involves daily yoga and Pilates (plus personalised body-composition assessments, tailored pescatarian or vegan menus, and daily massages). We’re taking part in only two of the customary five hikes, I’ve rescheduled the sunrise yoga for a more humane 9.30am, and I’m not even considering the wellness menus because there’s no way I’m forgoing the breakfast buffet: an orgy of gluten-rich, dairy-heavy, carb-loaded deliciousness that would make any self-respecting wellness guru weep. That would be la vita insanity.

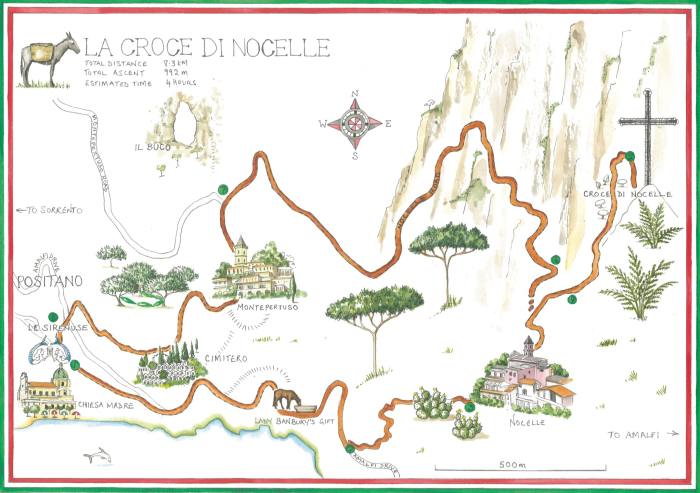

But you don’t have to sign up to a week’s wellness programme in order to pimp your Amalfi adventure for the healthier. Anyone can enjoy the myriad walks that interconnect the isolated hilltop villages. Sure, people are familiar with Il Sentiero degli Dei – The Path of the Gods, a former mule track that runs from Bomerano to Nocelle, just above Positano. But why shuffle up a hackneyed tourist path with hundreds of other people when just alongside it is the almost unknown Croce di Nocelle, a circular walk that takes you to the summit of Monte Vagnula, with its dramatic cliffside hideaways, before plunging back down through the village of Montepertuso and past the old merchants’ villas of Liparlati? Or there is the Casterna Forestale, a four-hour walk through cypress and pine forests which, between 1951 and 1976, was taken every Sunday by a priest from nearby Vico Equense – and where you are unlikely to encounter another soul.

The hills offer an entirely different perspective on a landscape that one could reduce to a few clichéd sunset views. But they aren’t easy. On the second day, walking alone with Giovanni because my daughter has refused to leave the hotel balcony (and who can blame her?), we ascend a seemingly endless concrete stairwell that is no more emotionally fulfilling than doing 30 minutes on a stairmaster. But when the concrete finally gives way to the mountain paths, one is immediately struck by the seabird’s vantage. The air feels different, smells different; it all looks almost Alpine in its lushness. There’s something psychologically reassuring, too, about walking ancient paths once used by villagers for whom there existed no other routes. Giovanni recalls his grandfather schlepping down the mountain with sides of pork to trade for firewood multiple times a week. Children would walk these paths to school. When people attribute the long lives and fortitude of Italians to their Mediterranean diet, they forget that, until recently, huge swaths of the population used to walk a daily marathon as well.

Back at the hotel, the massage therapist tends to my tender calf muscles with the ministrations of a sumo (regular Dolce Vitality guests have the option of Theragun “percussive” massages). I then consider leaping into the spa’s ice-cold plunge pool – but opt to eat a pizza and drink a Limoncello spritz instead. The morning yoga, led by a sweet American, Jennifer Warakomski, further saves my muscles from spastic atrophy.

Meanwhile, Positano has begun its gradual shift into the long winter hibernation. The beach jetty is dismantled and the boat crews start saying their goodbyes. There’s a chill in the evening, and I can book a restaurant with ease. I take a last dip in the Mediterranean and feel the exquisite melancholy that accompanies the final gasps of summer heat. After three days, I not only feel vital, I feel like a Roman goddess. Albeit one whose glute muscles are so sore she needs to grip her ass walking through the airport on her way home.

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Jo Ellison