A pharma partnership that brought a breakthrough in breast cancer

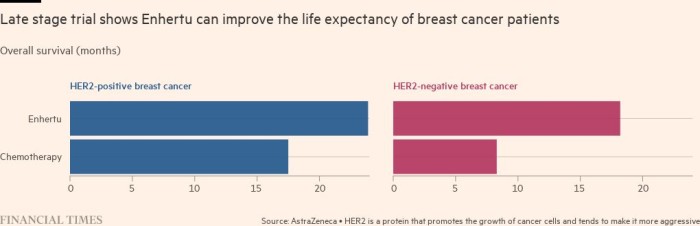

It is not often that a drug receives a standing ovation. When Daiichi Sankyo and AstraZeneca announced impressive results for their breast cancer treatment Enhertu, oncologists took to their feet to applaud.

“It was a goosebump moment, sending shivers down my spine,” said Susan Galbraith, who leads oncology research and development at AstraZeneca.

Ken Keller, chief executive of AZ’s Japanese partner on the drug, deliberately stood apart from his team at the American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting to see the mood of the crowd. “People had basically tears of joy in their eyes,” he said.

Baselga joined AstraZeneca in early 2019 as head of oncology research and development. He had been forced to resign from his post as physician-in-chief at New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering cancer centre because of a failure to disclose payments from healthcare companies, which the American Association for Cancer Research later concluded was “inadvertent”.

But while there, he had led the phase 2 trial for Enhertu, seeing first hand how it was helping patients. In his first week at AstraZeneca, he pushed the idea that AstraZeneca should have a partnership with Daiichi.

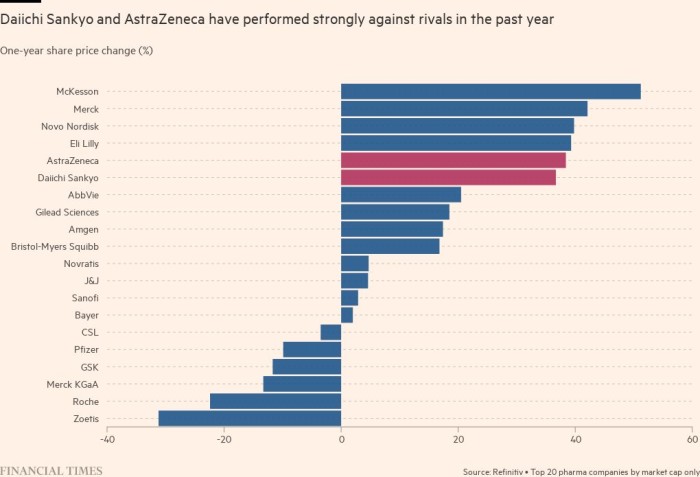

Daiichi is also creating other drugs based on the same platform as Enhertu, one of which is also part of a partnership with AstraZeneca. Gareth Powell, head of healthcare at specialist fund manager Polar Capital, said Enhertu has helped take AstraZeneca to a “whole new level in terms of growth potential” — and when sales take off, would ultimately boost margins at Daiichi.

“At some point, this product gets so big, you can’t spend it fast enough in terms of investment,” he said.

Analysts at Credit Suisse in London said the competition is at least three years behind. They believe if all of the treatments based on the platform that combines antibodies with a molecule to kill cancer cells in the pipeline are successful, it could add up to an opportunity as big as Merck’s blockbuster oncology drug Keytruda, which hit $17.2bn in sales in 2021. But they warned that investor expectations are already very high, so that if anything did go wrong, it could hit shares in AstraZeneca.

For patients, Enhertu promises time. Emma Fisher was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2016 when she was just 35, and two years later, found out it had spread. The average lifespan of someone with secondary breast cancer is two to five years.

Fisher’s private health insurance paid for the drug, but she testified to the UK’s National Institute of Clinical Excellence to try to persuade authorities to pay for it for everyone on the NHS. NICE now covers the drug for many patients with HER2-positive breast cancer, and will consider it for cancers with low levels of HER2 in 2023.

“Twelve months is a phenomenally long amount of time. It might not sound like a huge amount of time to somebody who doesn’t have incurable cancer. But for somebody with incurable cancer, an extra 12 months is everything,” she said.

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Hannah Kuchler