Bitter medicine: private equity moves into hospital ERs

Katie Porter did not go to the nearest hospital when, in the middle of her 2018 campaign for election to Congress, she began suffering debilitating pain in her abdomen.

“I knew enough to choose to go to an in-network emergency room when my appendix burst,” said Porter. In agony, she insisted on being taken to a hospital that was covered by her health insurance, even though it was further away.

“But my surgeon was out of network,” Porter added. Soon afterwards, she received a demand for about $3,000. “Enclosed with the bill were instructions on how to appeal my denial of coverage, because he’d seen this happen before.”

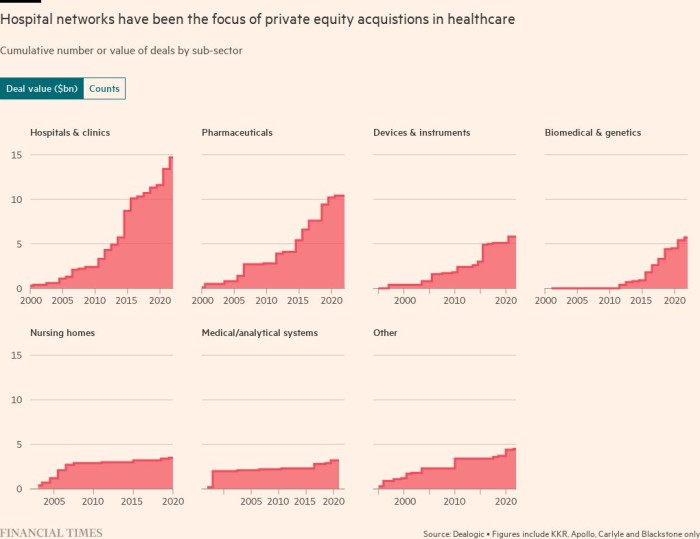

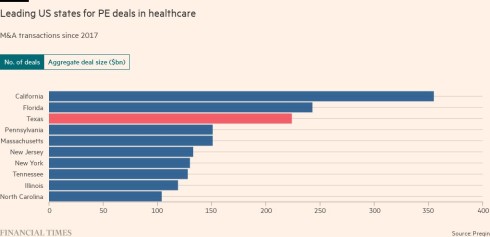

None of that has deterred Wall Street. Some private equity firms have focused on real estate, buying hospitals or urgent care centres. Others aim to make money buying up the companies that employ the doctors who work in many US hospitals.

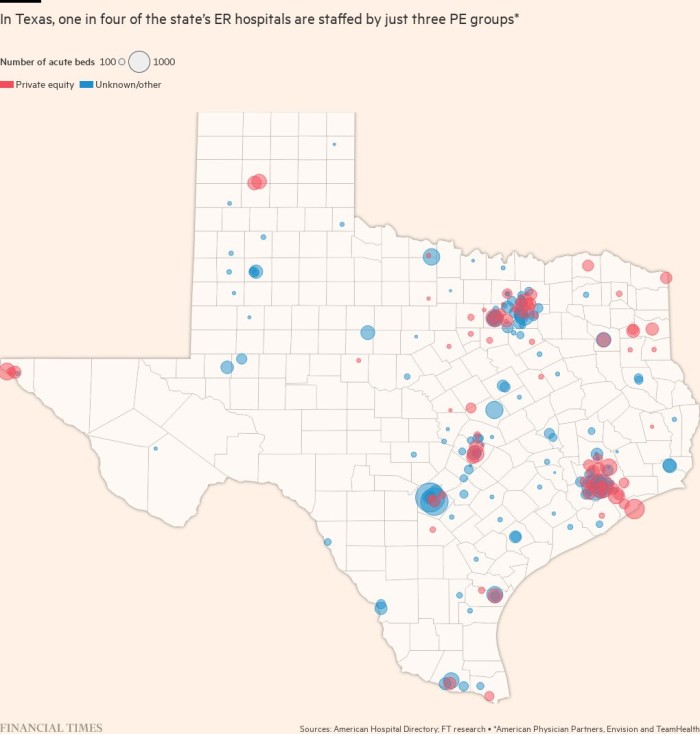

In Texas alone, three companies employ physicians that staff about one-quarter of the state’s 384 emergency rooms, a Financial Times review of job postings and regulatory records has found. That pattern is repeated across the country; a single company, TeamHealth, reported in 2017 that it provided emergency staffing to 17 per cent of the hospitals in its target market.

The PE model of emergency medicine

The doctors at Texoma Medical Center did not understand how private equity was going to change the way they worked until six months after the takeover.

“They came in, saying that nothing would change,” says one Texas doctor at an emergency department that was acquired by APP. “They didn’t do anything for six months, and then they put the model to work.”

That model is spelt out in a presentation given by APP executives as they sought a cash infusion of $580mn, a copy of which has been seen by the FT.

“Any potential negative impact resulting from the No Surprises Act” would be repaired, the presentation assured potential lenders, by cutting doctor wages, linking earnings to “productivity”, replacing doctors with less qualified personnel, and reducing staffing.

APP staffs at least a dozen emergency rooms in the Houston area, according to job advertisements published on the company’s website. Medics in the city are suing to extricate themselves from non-compete agreements similar to the one presented to doctors at Texoma, contending that APP’s efforts to cut costs and boost profits ended up blighting the emergency rooms with infighting and mismanagement.

One Houston doctor is accused of diverting performance payments that were due to his colleagues by billing insurance companies for more hours than he actually worked, according to a complaint filed in Harris county against several APP subsidiaries.

Another allegedly told colleagues to work while unwell, appearing to circumvent Covid protocols by communicating “his ‘4 Ms’: Motrin [ibuprofen], mask, man-up, must not test”, the complaint adds.

The APP subsidiaries named in the lawsuit have denied the allegations. APP and Brown Brothers Harriman declined to comment.

Escalating fights over doctor pay and working conditions may partly reflect an industry hit by rising costs, tougher reimbursement negotiations, and a shortage of patients as the risk of infection made many people wary of setting foot inside a hospital.

APP’s effort to raise new debt ultimately failed, forcing the company to negotiate a restructuring. After a lengthy negotiation, Envision this year used a complicated legal manoeuvre to present its creditors with a choice between accepting a haircut on its debt or being pushed to the bottom of the priority queue for repayment. A downgrade from rating agency Moody’s in October pushed TeamHealth deeper into junk territory.

Late last year, the medics at Texoma plotted a rebellion. Unwilling to embrace corporate management that they felt worsened patient care, yet reluctant to risk a costly lawsuit, they wrote a letter to the hospital’s chief executive, asking him to help them take back control of their emergency room.

“The acquisition felt more like a hostile takeover and had a devastating impact not only on our morale but in patient care and quality metrics as well,” said the letter, signed by five doctors last December, and seen by the FT.

The rebellion bore fruit. Texoma said in a statement that it “no longer contracted with APP for ER physician services.” APP’s removal paved the way for the doctors to set up their own staffing company at the hospital.

Such outcomes are rare. According to APP’s presentation to lenders, issued in November 2021, only one contract termination had occurred in the company’s history.

“We were able to pull it off,” one of the doctors said. “The spirit is back. It’s not about how much money they can take from you, it’s about taking care of patients.”

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Mark Vandevelde